SKILL-BUILDING EXERCISES

ACTIVITIES TO HELP IMPROVE YOUR SKILLS

SKILL BUILDING EXERCISES

Welcome to Critical Thinking Exercises

This section includes exercises that give you practice in critical thinking skills. You will find:

- Battlefield Critical Thinking Skills (BCTS) training that enables you to learn concepts and practice tactically-oriented critical thinking.

- A set of five modular exercises that give you practice in various aspects of critical thinking. Exercises include:

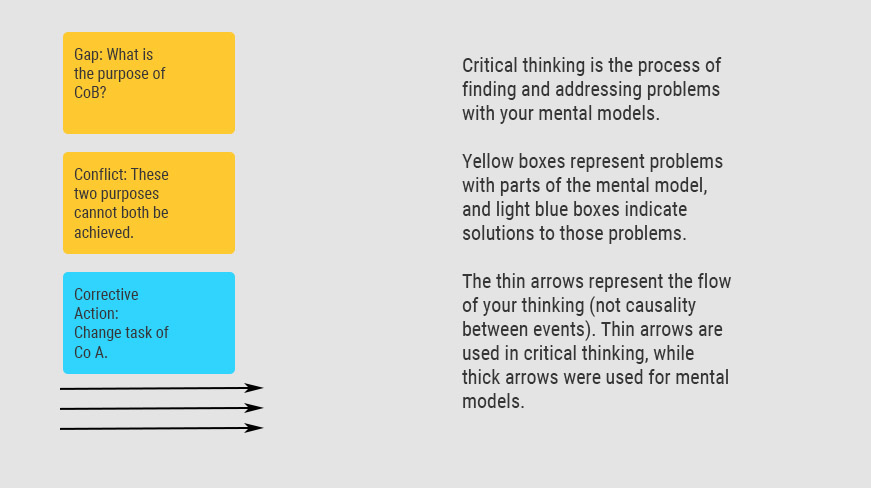

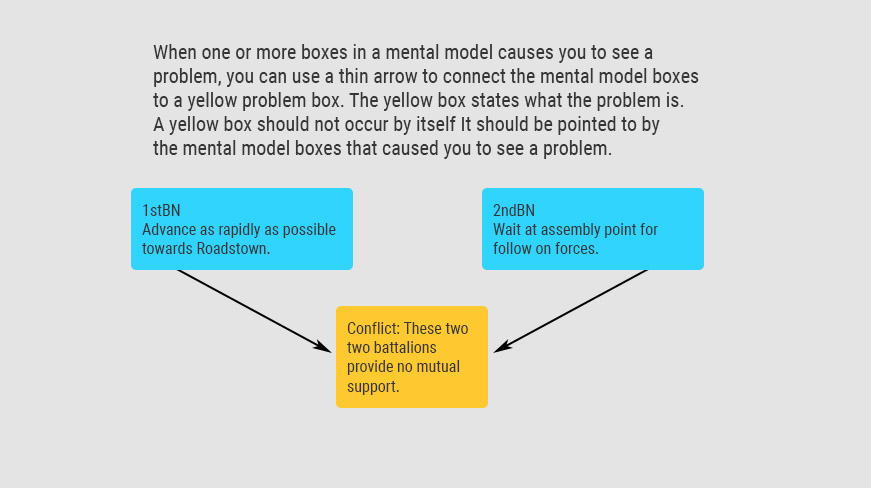

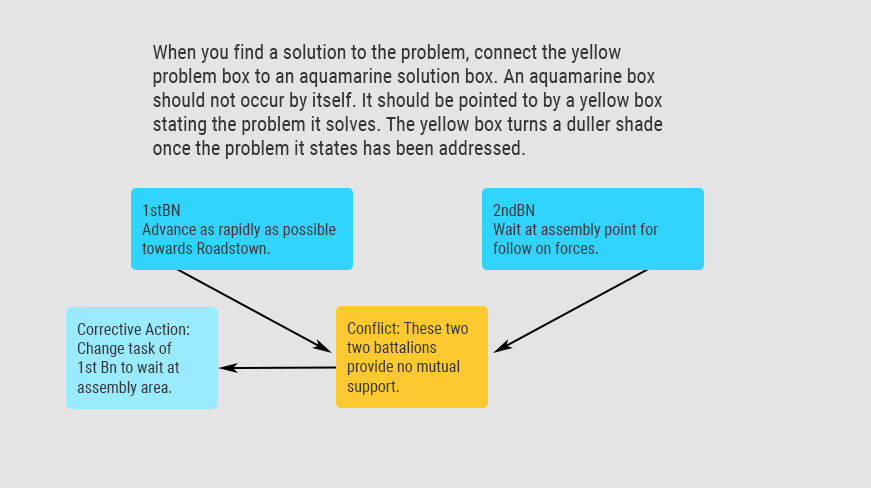

What is critical thinking?

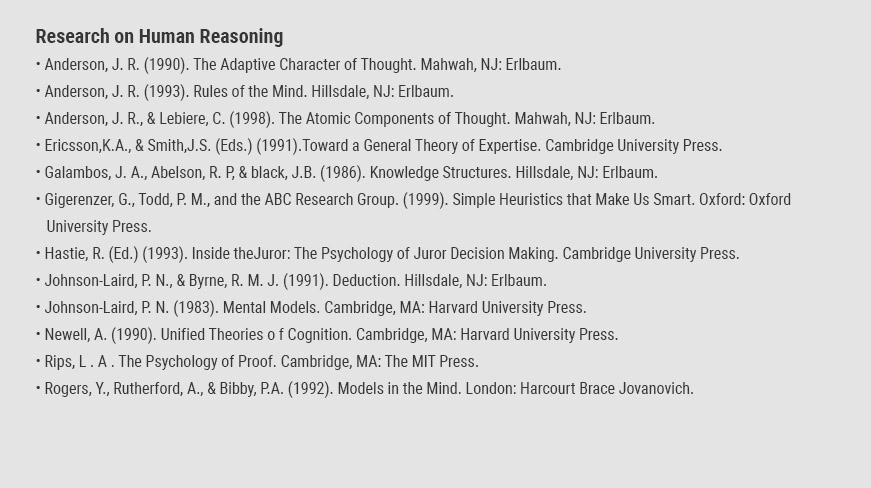

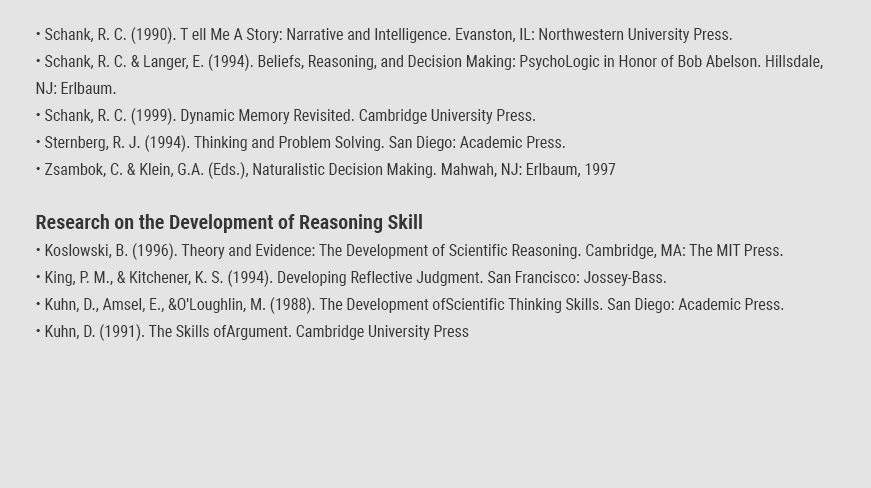

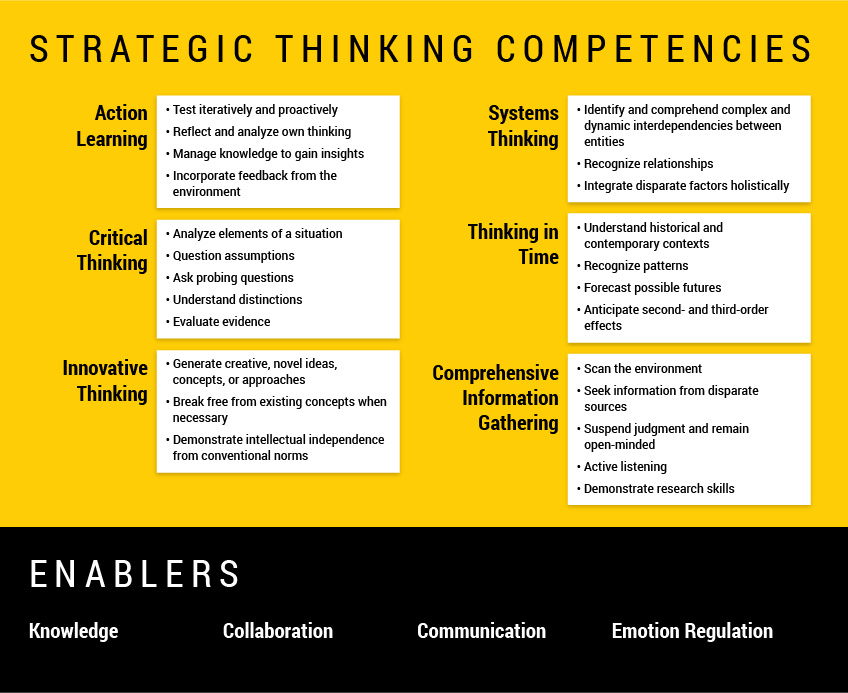

According to the University of Foreign Military & Cultural Studies (UFMCS) – specialists in Red Teaming – critical thinking is a process of deliberately analyzing and evaluating how we perceive and interpret the world in order to improve understanding and decision making. Similarly, Paul and Elder describe critical thinking as “the art of analyzing and evaluating thinking with a view to improving it.” A key aspect of critical thinking is developing the ability to ‘think about thinking’ as a way of understanding our own biases, perceptions, interpretations, mental models, ways of framing problems, and worldviews. According to research conducted by the U.S. Army Research Institute (ARI) for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, critical thinking is a fundamental skill for thinking strategically. Those who are effective strategic thinkers are able to analyze elements of a situation, question assumptions, ask probing questions, understand distinctions, and evaluate evidence.

Why does critical thinking matter?

Despite our best intentions, people often think in ways that are not optimal. We jump to conclusions, make assumptions that may be erroneous, take mental shortcuts, and allow cognitive biases to cloud our judgments and decisions. Critical thinking skills such as deconstructing arguments, challenging assumptions, examining perspectives, and exploring alternatives help Army leaders avoid some errors of judgement and maximize the quality of their decision-making.

What do the excercises involve?

The critical thinking exercises available on this site provide practice with various aspects of critical thinking.

The five modular critical thinking exercises include a combination of individual and group reflection, brief tutorials, practical challenges, expert perspectives, and guidance for application. The exercises provide tools and practice related to the following:

- Deconstructing arguments

- Critiquing a belief or position

- Identifying vulnerabilities in a plan

- Thinking critically about different worldviews

- Identifying root causes for better problem solving

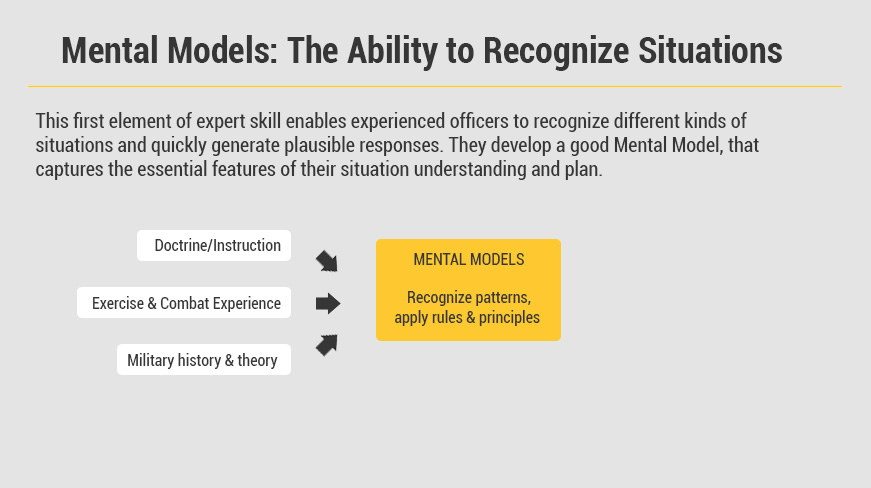

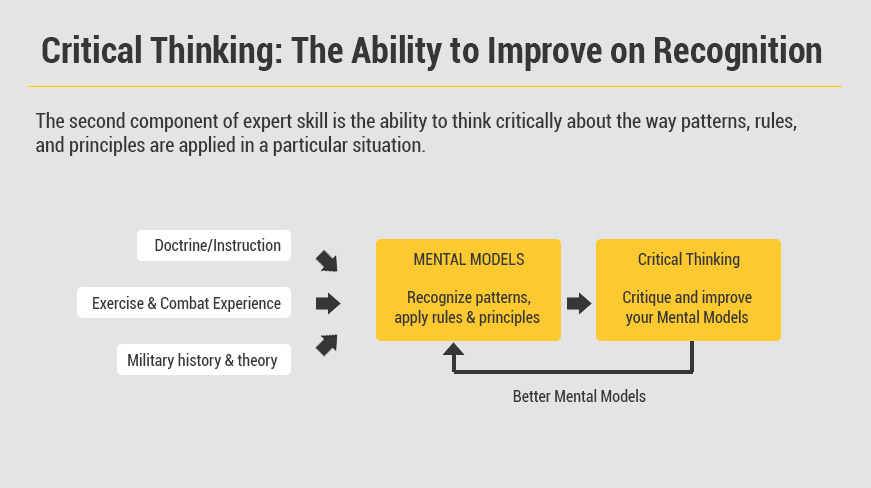

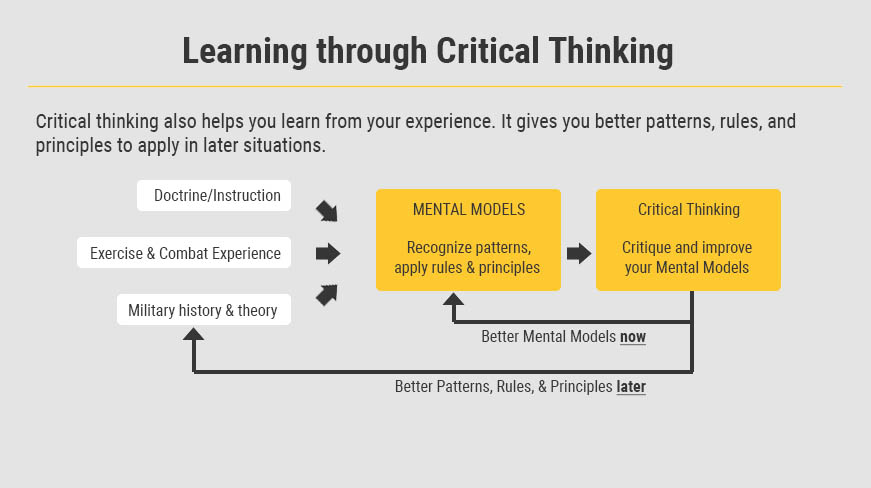

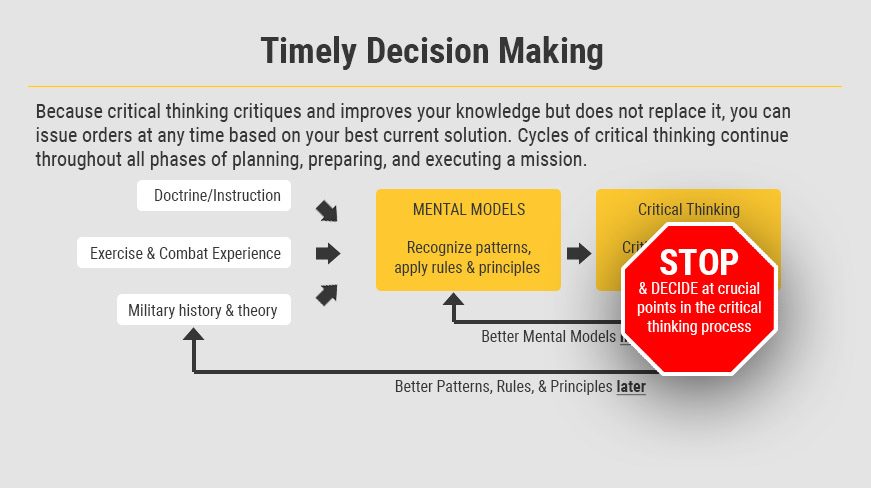

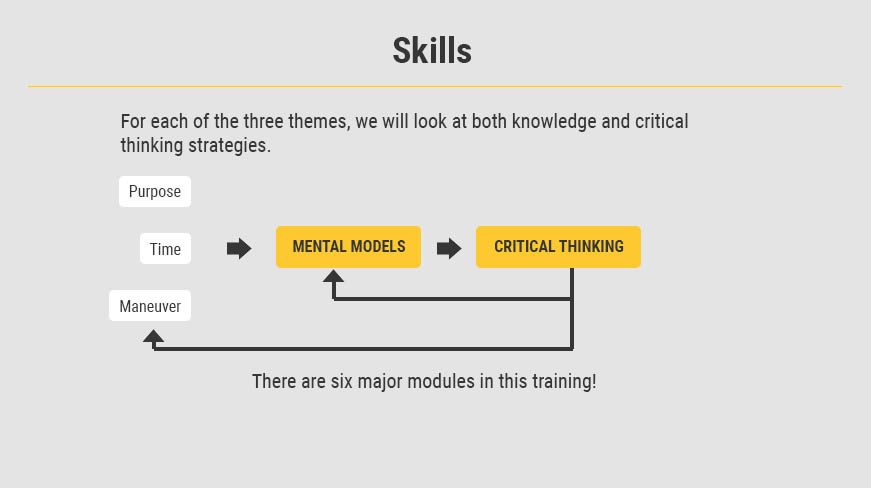

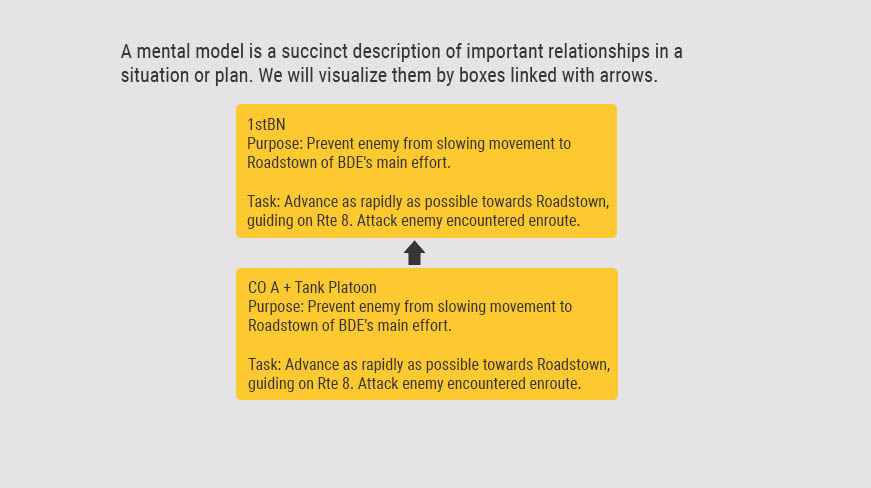

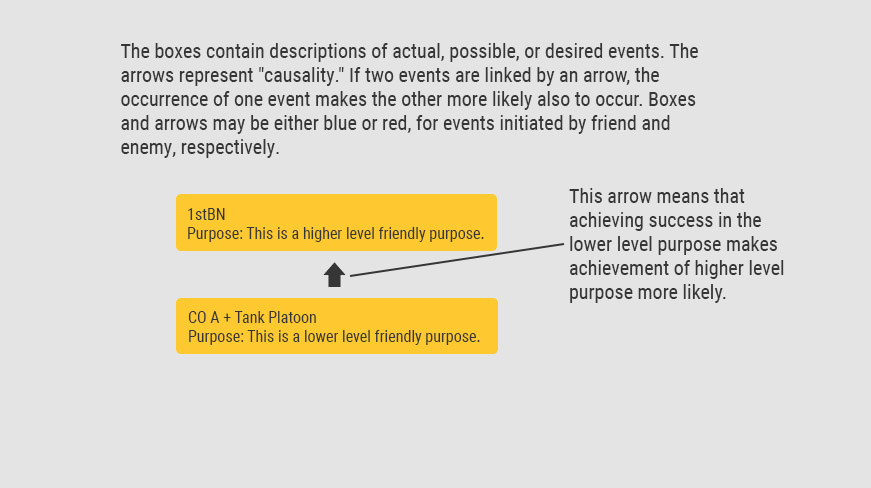

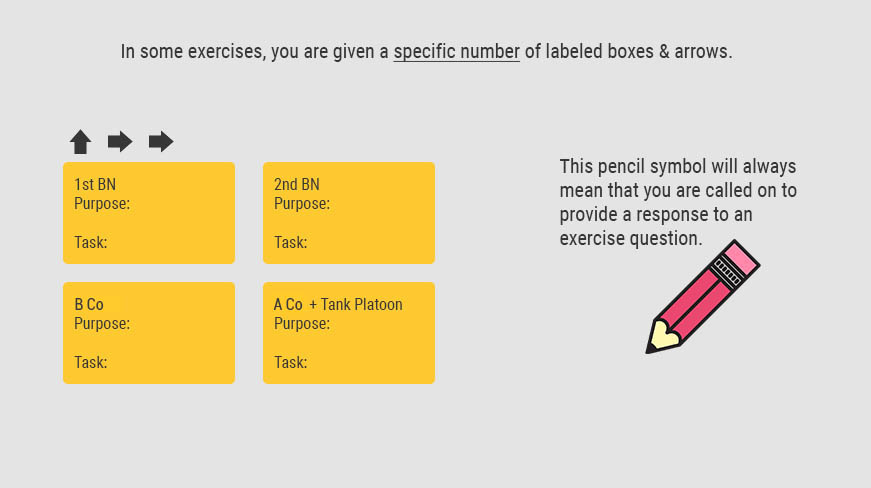

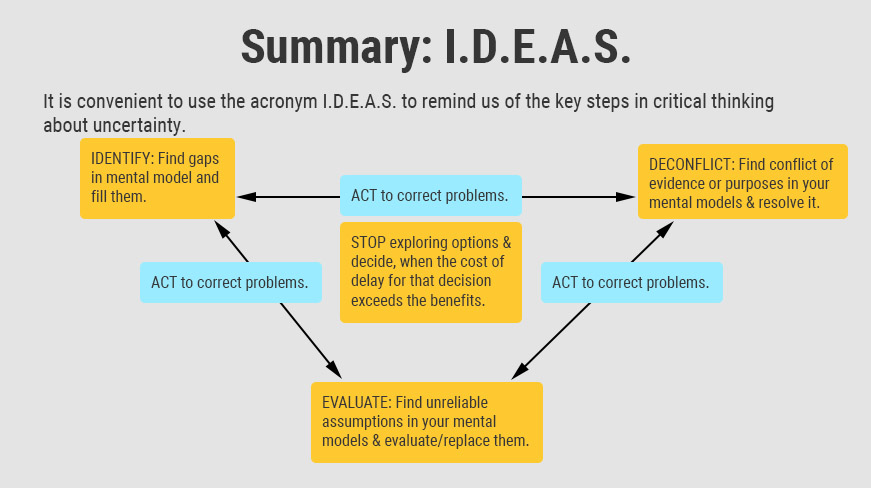

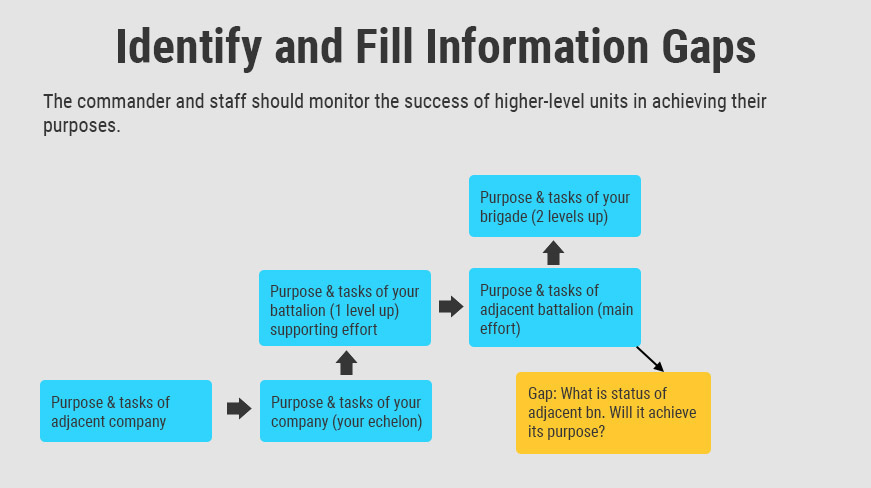

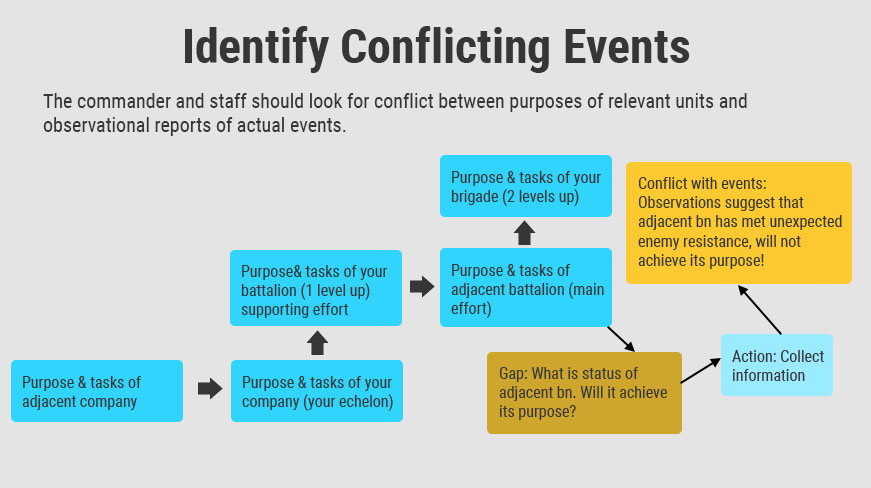

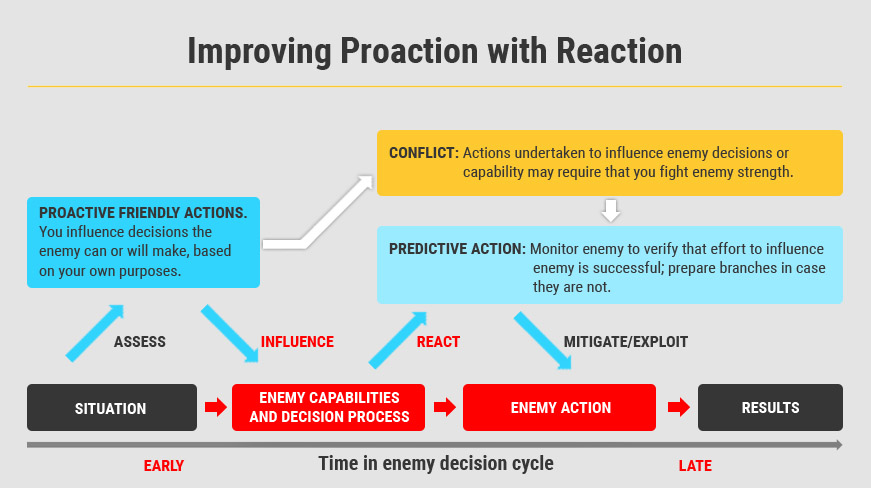

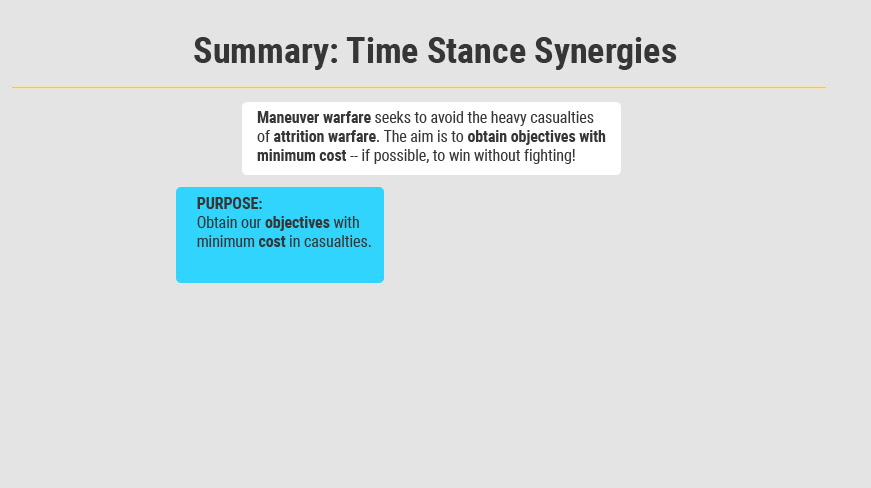

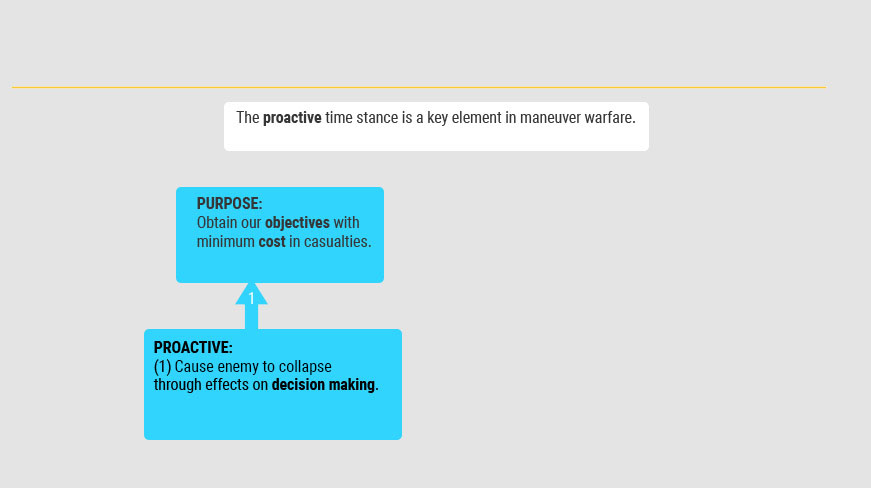

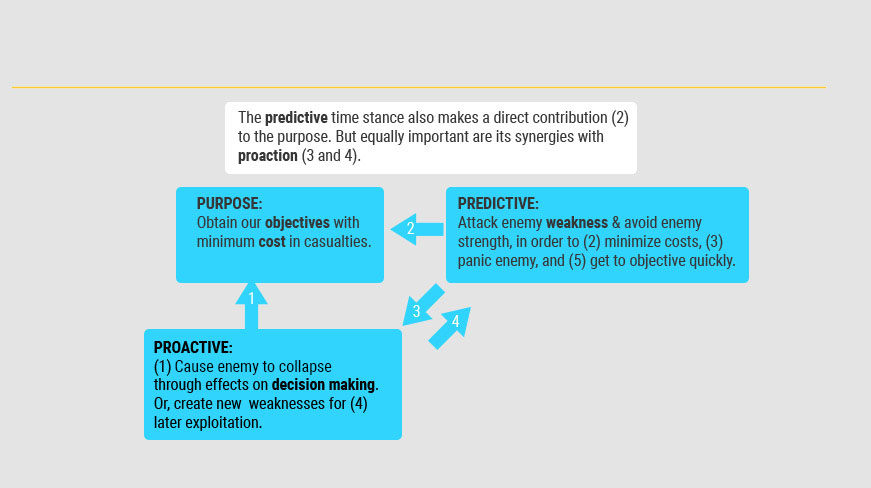

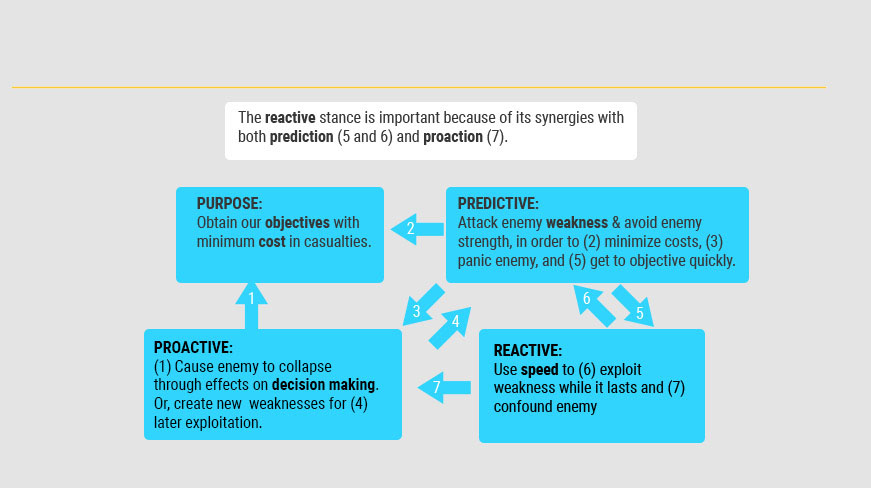

The Battlefield Critical Thinking Skills (BCTS) training enables you to learn about mental models and critical thinking associated with the battlefield thinking themes of purpose, time, and maneuver.

Argument Deconstruction

Welcome to Argument Deconstruction

(~3 minutes)

This exercise will give you practice in argument deconstruction, which is the thorough and systematic analysis of a persuasive position. Argument deconstruction helps you develop a better understanding of an argument by considering the issues, rationale, conclusions, evidence, and assumptions the argument contains or fails to address.

What’s the benefit of deconstructing an argument?

An argument is a set of statements, facts, or reasoning intended to establish a point of view. Arguments are typically made to convince or persuade others, but not all arguments are created equal. Deconstructing an argument helps to peel back the layers and determine if value conflicts, statistical errors, false assumptions, and/or erroneous conclusions exist in that argument. Applying this approach isn’t solely beneficial when considering others’ positions; it is also a valuable exercise to conduct with your own arguments. It can help you uncover weaknesses and strengthen the argument or case you are making.

Reflect: What makes argument deconstruction difficult?

(~5 minutes)

Take a moment to reflect on the prompts below. Capture your responses in the text field.

- When are you presented with arguments and opinions in the context of your work?

- How do you evaluate the value and credibility of an argument?

- What is the most difficult part of deconstructing an argument?

| Enter text here |

Now that you have finished your reflection, you can click Expert Response to see what experts say about common challenges relating to deconstructing an argument. Did you identify any of the same challenges?

Deconstructing arguments can be challenging for several reasons:

- Arguments can be skillfully hidden and presented as fact. It requires strong critical thinking skills to spot weak or distorted evidence, fallacies, and unwarranted assumptions.

- It can be particularly difficult to deconstruct and see weaknesses in an argument that aligns with one’s own beliefs, values, and opinions.

As with any skill, practice and reflection will enhance your ability to understand a different perspective more deeply.

An Example

(~3 minutes)

Let’s look at an example.

Imagine that your friend shares a post on social media that states that ‘vaccines are dangerous, and that people should not take them.’ The post says that ‘vaccines contain harmful chemicals that can cause autism in infants, and they can make adults very sick.’ She also shared an article to support her point.

As a new parent, this information is troubling to you, and you are concerned for your friend who posted this information. You decide to deconstruct your friend’s argument to get to the bottom of it.

To begin, you identify these core aspects of the argument:

| Issue | Whether to get vaccinated |

|---|---|

| Position | You should not get your children or yourself vaccinated. |

| Argument(s) | Vaccinations contain harmful chemicals that can cause autism in infants and can cause serious illness in adults. |

| Evidence | A single published article. |

Then you continue the process of deconstructing the argument by considering the following reflection prompts:

| What are the characteristics of the evidence provided? |

|

|---|---|

| What evidence is omitted? |

|

| What is a potential counterargument? |

|

By deconstructing this argument, you are better able to understand your friend’s argument and stop the spread of disinformation on social media.

Take the challenge

(~10 - 15 minutes)

It's time to practice deconstructing an argument.

Your challenge is this

First, read the following persuasive article about the Pentagon.

Then, use the argument deconstruction framework to understand this person’s position and arguments.

Close the Pentagon — it’s too big of a target

Source: James Hasik, Defense News, August 31, 2020

In 2001, an attack against one of the five sides of the Pentagon killed 125 and forced a partial evacuation. The Defense Department showed impressive resilience: Even as one side of the building collapsed, its command center kept functioning. Conflict yet continues, in part because al-Qaida has few fixed targets to destroy. Thus, for three decades, America’s wars have seemed either drive-by shootings or questionable quagmires. The next war that matters may be neither.

In 2001, finding the Pentagon at 500 knots may have been challenging for the suicide pilot, but not today for a cruise missile. In 2019, half of Saudi Arabia’s oil refining was temporarily incapacitated by a barrage of just two dozen Iranian missiles. More ominous was the total failure of the kingdom’s air defenses to defend against or even detect the attack before the first impact.

In early 2020, the present pandemic forced a more thorough evacuation. The Pentagon’s command center has functioned, but most other activities have moved offsite, and substantially to private homes. Around the military and its contractors, remote work has expanded tenfold, to about 1 million people. Defense Secretary Mark Esper has expressed surprise at how well the arrangement has been working. Peter Ranks, his deputy chief information officer, says that productivity has not suffered.

This matches a broader reality. About half the American workforce is working remotely, and remote work is becoming permanent.

For the military today, reading secrets still generally requires a trip to a mostly empty office. However, the U.S. Air Force and Defense Information Systems Agency have initiated pilot programs to conduct even classified work remotely. Information security remains vexing, but unless the Defense Department wants to rely entirely on couriers, its cyber vulnerabilities will require intense attention anyway.

Retired Adm. James Stavridis recently wrote of the value of physical proximity, as “we cannot ‘Zoom’ trust.” The safety of social distancing can lead, he argued, to the disconnection of real social distance. That sounds bad, but many people have been working remotely for much of the past 20 years with manageable difficulties. As more of the world chooses to go remote, managers and social scientists will learn yet more about how to do it right.

Indeed, these difficulties must be managed because the alternative is frightening.

Today, Russia and China have masses of cruise missiles, dozens of submarines for launching them and global navigation satellite systems for guiding them. Attacking fixed targets is first a matter of mission planning, and the entire world has been thoroughly mapped. It is second a matter of avoiding air defenses, and of this there is little around North America. In that context, contemplate the possibility of not a singular attack upon the Pentagon, but one with dozens of missiles slamming into all fives sides, and down through the “bullseye” center court.

In private conversations, former defense officials keep reminding me that our war-fighting systems are too dependent on highly concentrated and easily located airfields, ports, depots and command centers. In contrast, America’s adversaries are either going mobile or deeply burying facilities. The Pentagon is neither mobile nor deeply buried.

So why have a Pentagon at all? Why maintain that highly concentrated target?

It’s certainly not for recruiting and retention. In closing the Pentagon, the military could stop rotating staff officers in and out of northern Virginia. Remote work from current stations would remove the disruptions of yet another change of station, particularly late in careers when officers’ children are often advancing through high school.

It’s also not for better decision-making. In his valedictory complaint in Wired, John Kroger, the Navy’s recently departed chief of learning, described the Pentagon as “a threat to national security.” With its concentrated culture of scripted updates, hostility to analysis and mid-century office technologies, “The Building” is much of the problem. Emptying it permanently could help multiple, and hopefully better, military cultures flourish.

What would we do with an empty Pentagon? We have options. Arlington National Cemetery is running out of space. Perhaps a professional sports team will eventually want a centrally located venue. Northern Virginia could always use another park. What really matters is dispersing that concentration of leadership beyond one building in northern Virginia, lest we someday lose it all at once.

James Hasik is a senior research fellow at the Center for Government Contracting at George Mason University, and a senior fellow at the Scowcroft Center on Security and Strategy at The Atlantic Council.

Now that you’ve finished reading the article, spend a few minutes answering some initial questions about the argument offered in the piece you read.

- Issue: What is the topic or decision under consideration?

- Position: What is the position or opinion presented?

- Argument(s): What argument is the author making?

- Evidence: What evidence or information does the author offer in support of the argument? For example: research studies, statistics, testimonials, anecdotes and case examples, personal experience.

Capture each of those components in the text fields below.

| Issue |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Position |

|

|

| Argument(s) |

|

|

| Evidence |

|

When you have described the component parts, spend a few minutes reflecting on the following -

- Point of view: How would you describe the author’s point of view?

- Assumptions: What assumptions does the author make?

- Questions raised: What does the author raise as key questions that need to be addressed?

- Available evidence: What evidence or information does the author offer in support of the argument? For example: research studies, statistics, testimonials, anecdotes and case examples, personal experience.

- Missing evidence: Is there evidence or information that is missing? Data that you would expect but isn’t provided?

- Alternative interpretation: Is the evidence/information provided open to different interpretation and/or conclusion?

Enter your responses in the text field below:

| Author’s point of view |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Author’s assumptions |

|

|

| Questions raised |

|

|

| Missing evidence |

|

|

| Alternative interpretations |

|

Based on this analysis, what could make this argument stronger?

Enter your responses in the text field below:

| Enter text here |

Reflect on the exercise

(~5 minutes)

Now that you’ve had a chance to deconstruct an argument it’s time to think about the experience of thinking critically about an argument or opinion. Consider the following questions and capture your responses in the text field below.

- What aspects of the opinion piece do you see differently now?

- What have you learned or become aware of that hadn’t occurred to you before?

- In what ways do you see argument deconstruction as being useful when you are expressing a point of view or hope to persuade someone?

| Enter text here |

Meet with your peers

(~20 minutes)

Get together with a peer group to share your responses to the Argument Deconstruction exercise and some of the insights you gained. After each person shares their responses and insights, discuss the following questions as a group:

- What have you gained from deconstructing an argument?

- Think about the different aspects of the argument (issue, position, argument(s), evidence) you considered. How is breaking the argument down in this way helpful?

- In what ways do you anticipate using argument deconstruction in your daily operations?

Additional practice with argument deconstruction

Select and view one of the following videos of your choice.

The Military Case for Sharing Knowledge

(Stanley McChrystal; ~6 minutes)

A New Mission for Veterans

(Jake Wood, ~ 4 minutes)

Behind China’s Influence in Africa

(Council on Foreign relations; ~2 minutes)

Complete the deconstruction process with the argument made in the video. Use the framework below to help you.

- Issue: What is the topic or decision under consideration?

- Position: What is the position or opinion presented?

- Argument(s): What argument is the presenter making?

- Evidence: What evidence or information does the presenter offer in support of the argument? For example: research studies, statistics, testimonials, anecdotes and case examples, personal experience.

Capture each of those components in the text fields below.

| Argument Component | Your Summary of the Component | |

|---|---|---|

| Issue |

|

|

| Position |

|

|

| Argument(s) |

|

|

| Evidence |

|

When you have described the component parts, spend a few minutes reflecting on the following -

- Point of view: How would you describe the author’s point of view?

- Assumptions: What assumptions does the author make?

- Questions raised: What does the author raise as key questions that need to be addressed?

- Missing information: Are there factors or pieces of information that strike you as important that the author fails to acknowledge?

- Missing evidence: Is there evidence or information that is missing? Data that you would expect but isn’t provided?

- Interpretation: Is the evidence/information provided open to different interpretation and/or conclusion?

Enter your responses in the text field below:

| Presenter’s point of view |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Presenter’s assumptions |

|

|

| Questions raised |

|

|

| Missing evidence |

|

|

| Alternative interpretations |

|

Based on this analysis, what could make this argument stronger?

Enter your responses in the text field below:

| Enter text here |

Now, share your argument deconstruction with a peer or mentor.

Ask your peer or mentor to challenge your thinking as you share your deconstruction framework with them.

When you’ve finished this activity, click Finished.

Put your argument deconstruction skills to work

(~10 minutes)

Now, it’s time to try out argument deconstructions in your work.

In this activity, you will reflect on a debate or difference of opinion that you have experienced at work, school, or your personal life.

Here’s what to do:

- Identify the issue or topic at the center of the debate, and the reasons and conclusion from your point of view.

- Once you’ve identified these aspects, consider the evidence you have brought to the topic, your assumptions, and how well they support your conclusion.

- Reflect on ways to make your point of view clearer, more logical, and more credible.

- Capture your insights in the text field below or in your notebook.

| Enter text here |

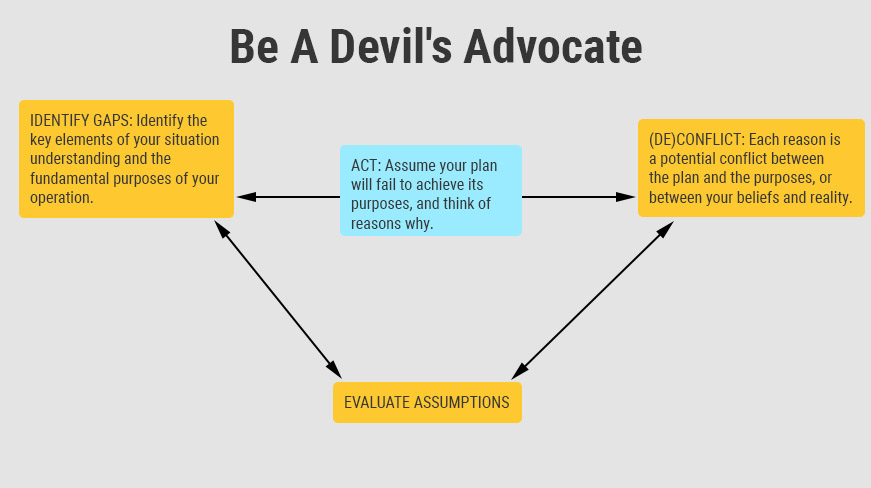

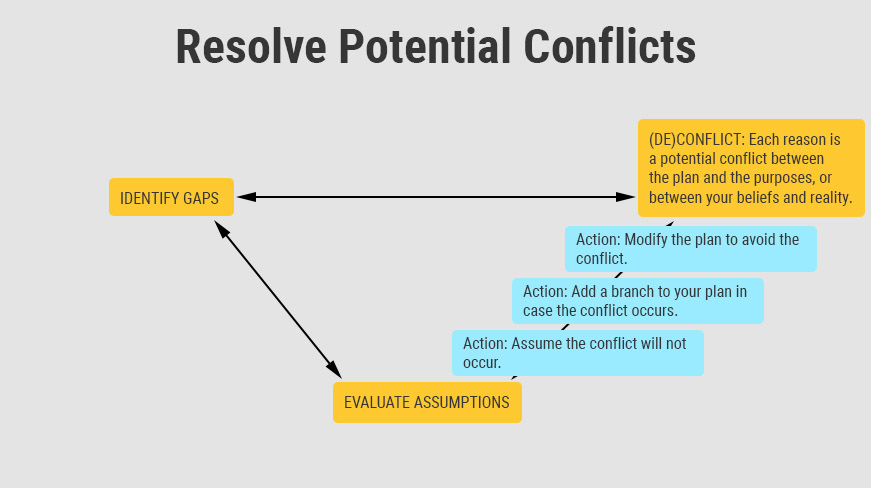

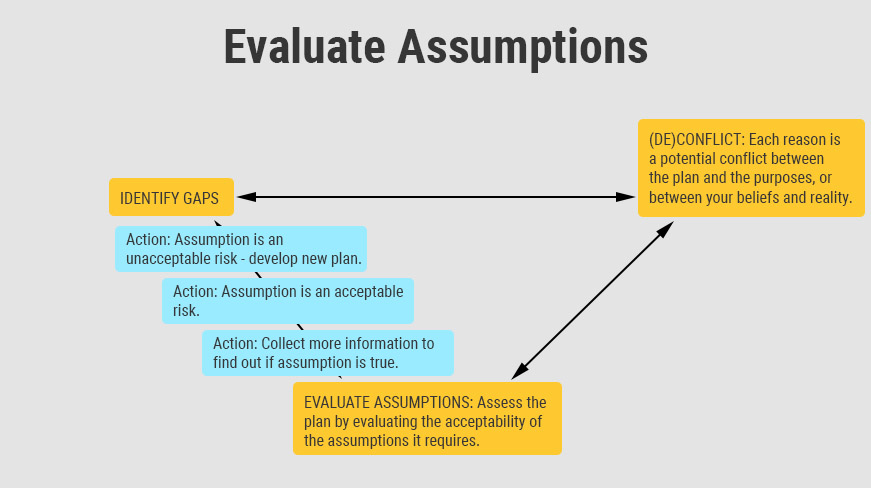

Devil’s Advocacy

Welcome to Devil’s Advocacy

(~3 minutes)

This exercise will give you practice in challenging a fundamental belief or strongly-held view. You will practice building a case for an alternative explanation that opposes a stated position.

What's the benefit of challenging a strongly-held view?

When solving problems and creating plans, we sometimes form a view or take a position prematurely, without first considering alternative perspectives. We often fall prey to confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is the tendency to favor information and ideas that confirm or justify our existing beliefs and to minimize evidence that might contradict those beliefs. For example, if we believe that GE appliances are the best made and most reliable appliances on the market, we may look for and see only customer testimonials that confirm this. We may overlook, dismiss, or give less weight to any consumer claims to the contrary.

Taking on the perspective of the “devil’s advocate” can help to counter confirmation bias. Playing the “devil’s advocate” involves intentionally taking a different perspective or minority point of view, even if you do not necessarily agree with that view. It helps to expose implicit assumptions or faulty reasoning, particularly when beliefs or assertions have been made hastily (e.g., when your team may have “jumped to conclusions”), and to consider how a different set of assumptions might lead to a different view or belief. It also helps illuminate evidence that was either intentionally or unintentionally disregarded or ignored in the first place.

Reflect: What makes it hard to challenge beliefs or views?

(~5 minutes)

|

Take a moment to reflect on the prompt below. Capture your responses in the text field below.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Now that you’ve finished your reflection, you can click Expert Response to see what experts say is difficult about challenging deeply held assumptions and beliefs. Did you identify any of the same difficulties?

Questioning assumptions and challenging a strongly held view can be difficult for several reasons:

- When we solve problems, it’s common to fall prey to confirmation bias as described above. [Click here to learn more about confirmation bias].

- We tend to perceive what we expect to perceive.

- We tend to value information that is consistent with our views and reject or overlook information that is not.

- We can easily become wedded to a pre-existing plan, perspective, person’s reputation, etc., which keeps us from thinking critically about that plan, perspective, person, etc.

- We often do not stop to consider what assumptions we are making and why. Questioning assumptions starts with realizing you are, in fact, making an assumption.

Take the challenge

(~5 - 10 minutes)

It’s time to practice playing the devil’s advocate.

Your challenge is this:

Think about a position that your unit, your class, your team, or your family is taking right now, along with the reasons for that position. It can be an underlying position that is rarely discussed or questioned. It can also be a position you have reached, relevant to a selected course of action.

A few examples of positions to help spur your thinking include:

- “The U.S. Federal Government should not directly fund private schools.”

- “Florida is the best place for a family vacation.”

- “National service should be mandatory.”

- “Co-ed schools offer a superior educational environment.”

- “Senior military leaders should refrain from voting in presidential elections."

An example of the reasons for a belief or position would be:

“Florida is the best place for a family vacation because….

Once you’ve thought of a position your unit, class, team, or family is currently taking, capture that position – and the reasons for it - in the text field below. |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

Now, state an opposing position. For example, the positions noted above in their opposite form are:

For the position you noted above, state the opposing position in the text field below. |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

Next, spend approximately 5 minutes considering the reasons why the opposing position is valid. Capture your reasons in the text field below.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Critique the original position

(~5 - 10 minutes)

Now your challenge is to assess and critique the original belief or position you chose to work with in the previous challenge.

Consider and document in the text field below:

- Weakest points in your original stated position.

- Information or considerations in the original stated position that may have been overlooked.

- Information or considerations that are missing from the original stated position.

- Any implicit assumptions upon which the original stated position rests.

| Weakest points in terms of reasoning |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Overlooked information |

|

|

| Missing information or considerations |

|

|

| Implicit Assumptions |

|

Revise your position

(~5 minutes)

|

You’ve now had a chance to state a position, take an opposing view of that position, and critique that position.

Capture your response in the text box below. |

|---|

| Enter text here |

Reflect on the exercise

(~5 minutes)

|

Now that you’ve had a chance to challenge a belief, it’s time to think about your experience doing so. Consider the following questions and capture your responses in the text field below.

Enter your reflections in the text field: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

Ask a mentor or peer

(~10 - 15 minutes)

|

There is much to learn from others.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

Now, ask your mentor or peer to share with you an example from their own lived experience when they challenged an underlying belief or position within their unit, planning team, or classroom. Solicit their reflections on the following:

Capture what you learn from the conversation in the text field below or in a notebook for future reference. |

|---|

| Enter text here |

Put your devil's advocacy skill to work

(~10 minutes)

Now, it’s time to try out your devil’s advocacy skills in your work.

In this activity, you will apply the devil’s advocacy approach. Here’s what to do:

- In your next unit planning exercise or classroom discussion, take on the role of devil’s advocate to help the team arrive at its plan or decision. (Note: Depending on the climate of your unit or classroom, you may want to discuss this with your leader ahead of time to ensure their support).

- As the team is discussing the plan, take note of a stated position or implicit belief underlying the discussion or plan.

- In your head or in a notebook, restate the position or belief in its opposing form, along with the reasons the opposing position or belief is true.

- Jot down any weak, missing, or overlooked information or reasoning from the originally stated position.

- Share the opposing view and reasoning with your team. As you present the information, you may want to start by explicitly stating: “I’m going to play devil’s advocate for a moment…”

|

Following this experience, reflect individually or with a peer on what happened when you shared the opposing point of view.

Capture any lessons-learned in the text field below or in your notebook. |

|---|

| Enter text here |

4 Ways of Seeing

Welcome to 4 Ways of Seeing

(~3 minutes)

This exercise will give you practice in considering different perspectives, assumptions, and motivations of different entities (e.g., people, groups, organizations, nations). You will also practice identifying potential misunderstandings and leverage points for working most productively with different entities.

Intentionally considering multiple perspectives, including your own, can help you identify sources of potential misunderstanding and conflict. By better understanding how others with opposing views see the world (including their values, motivations, and needs), you can better understand the nature of the disagreement and generate mutually beneficial solutions to resolve conflict.

Reflect: The challenge of considering multiple perspectives

(~5 minutes)

|

Take a moment to reflect on the prompts below. Capture your responses in the text field below.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Now that you’ve finished your reflection, click Expert Response to see what experts say about common challenges relating to perspective-taking. Did you identify any of the same challenges?

Considering multiple perspectives can be challenging for several reasons:

- We all have biases. Putting aside our own assumptions, attitudes, and beliefs can be a significant challenge.

- Recognizing differing views is only a first step. Appreciating the other perspective and the key factors that influence it is an even greater challenge.

- Cultural attitudes, beliefs, and ways of thinking heavily influence our perspectives and understanding. It may be especially difficult to take on the perspective of someone else whose culture is completely outside of your own cultural norms.

As with any skill, practice and reflection will enhance your ability to understand a different perspective more deeply.

Get warmed up: Consider an example

(~3 minutes)

Let’s explore an example of two groups with different perspectives.

Imagine you are comparing the perspective of traditional gas car owners versus electric car owners. To conduct the 4 Ways of Seeing exercise, you would consider the following:

- How A views itself: How traditional gas car owners view themselves

- How B views itself: How electric car owners view themselves

- How A views B: How traditional gas car owners view electric car owners

- How B views A: How electric car owners view traditional gas car owners

Now, take a look at the 2x2 grid that follows to see a simple illustration of the 4 Ways of Seeing approach, capturing views of traditional car owners and electric car owners:

How gas car owners view themselves:

- Traditional in terms of car selection

- Supportive of fossil fuel industry

- Wants a cheaper car up front

- Accepts regular maintenance as part of car ownership

- Likes to stick with what they are familiar with

- Finds electric vehicles uncertain

How gas car owners view electric car owners:

- Not practical

- Snobs

- Risk takers

How electric car owners view themselves:

- Environmentally conscious

- Unsupportive of fossil fuel industry

- Willing to pay more up front

- Likes saving on maintenance

- Sees car as status symbol

- Enjoys the responsiveness/immediate acceleration

- Fun to drive

How electric car owners view gas car owners:

- Not environmentally conscious

- Short-sighted/Narrow-minded

- Rigidly old-fashioned

Of course, we’re making some generalizations here to illustrate the 4 Ways of Seeing skill. But this framework can be a useful tool as you practice perspective-taking.

Practice considering multiple perspectives

(~5 minutes)

Now, you will get an opportunity to try out the 4 Ways of Seeing approach.

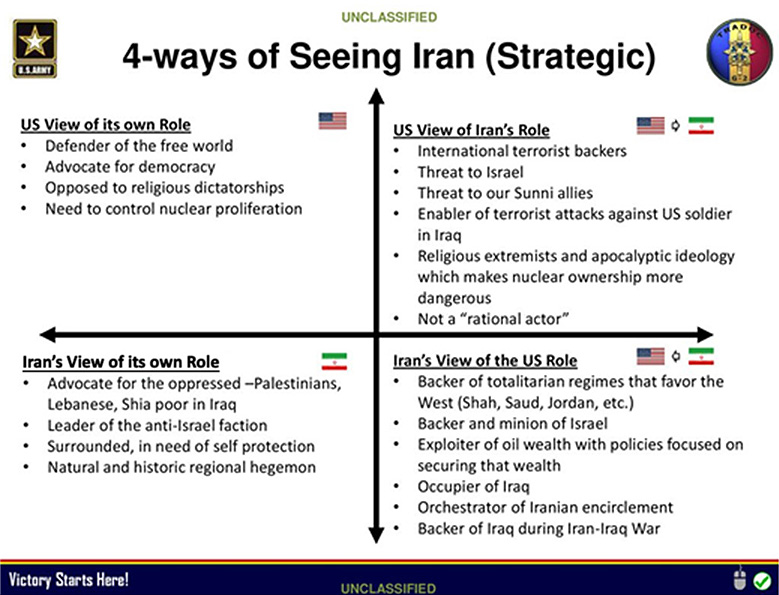

Imagine you’ve been tasked with understanding the differing perspectives between the United States and Iran with respect to their role in global security. Spend some time researching these two perspectives online, and then fill in the chart below.

|

US View of its own role How does the US view itself? |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

US View of Iran’s role How does Iran views itself? |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

Iran’s View of its own role How does the US view Iran? |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

Iran’s View of the US role How does Iran view the US? |

|---|

| Enter text here |

How do your responses to this exercise compare to what experts identified for each perspective? What do you have in common with the experts? What aspects of each perspective did you miss?

Source: https://www.google.com/search?q=four+ways+of+seeing+army&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjmrPXursPrAhXVKs0KHcH9Cg0Q_AUoAnoECAwQBA&biw=1536&bih=694#imgrc=2TYEluZmXKJmZM

Important to note is that when dealing with complex problems, we are typically considering more than two entities. As you use this framework, you can add additional entities to consider the differing perspectives, beliefs, values, and motivations of multiple entities.

Once you’ve completed your comparison, click Finished.

Take the challenge

(~10 - 15 minutes)

Now that you have seen an example and practiced the 4 Ways of Seeing exercise, read the following scenario and apply the 4 Ways of Seeing approach to the situation.

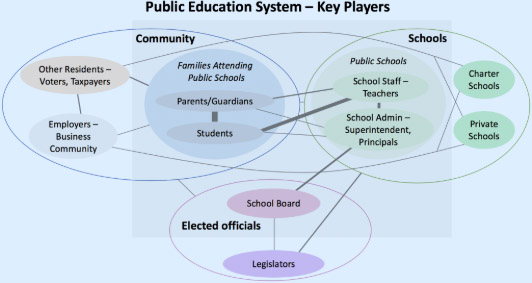

Scenario:

The debate between the efficacy of public versus charter schools in US K-12 education is ongoing. Proponents of charter school education cite that parents should have the opportunity to choose where their children go to school, and states should be willing to fund those choices. They do not believe that their children should be limited to the quality of the school based on the school district where they physically live. They see the alternative education experiences their children receive in charter schools as superior to the education their child might receive in the public school system. Since charter schools are not heavily regulated, charter schools are often able to employ alternative or innovative approaches to education that might not be possible within the heavily regulated confines of the public school system.

Proponents of public education believe that funneling funds away from public schools to fund charter schools is harmful to school districts who desperately need that funding from states and provides an insufficient education to students who attend charter schools. Public school proponents believe that charter school students often ‘slip through the cracks’ and special needs might be entirely missed altogether. Fewer resources mean that the charter schools lack the support structures and services that public schools provide. When charter school students re-enter the public school system (and they frequently do), public school teachers often find that the students are not meeting the state standards for their grade level, and do not have the skill development or breadth of experience that their public school counterparts have had. Instead, public school teachers often need to ‘catch up’ the charter school students to try to help them get up to speed to the public education standards. Many stories of poorly regulated charter schools and misappropriated funds leave public school advocates frustrated with their states for shielding and enabling charter schools to provide sub-par educations to their students.

Your challenge is this:

Now, spend 10-15 minutes reflecting on the four quadrants in the table below. Fill them in one at a time. Use the prompts below, but don’t feel limited to these.

Starter Questions

- How does each side view the situation?

- What perspective does each hold about public versus charter schools?

- What beliefs might be driving the behavior of each side?

Capture your responses in the four quadrants below.

|

Group A: Public School Advocates How public school advocates view themselves |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

Group B: Charter School Advocates How public school advocates view charter school advocates |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

How charter school advocates view themselves |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

How charter school advocates view public school advocates |

|---|

| Enter text here |

When you have filled in all four quadrants, take a few minutes to reflect on the following:

- What are some commonalities between the two groups?

- What are some differences between them?

- Are there consistent areas of conflict between them?

- Are there topics or issues where they agree?

- Where might there be misunderstandings between them?

Enter your responses in the text field below:

| Things they have in common: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

| Ways they are different: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

| Areas of conflict: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

| Areas of agreement: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

| Possible misunderstandings: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

Based on your analysis, identify 2-3 actions that might decrease discord and improve relations between them.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Reflect on the exercise

(~5 minutes)

Now that you’ve had a couple chances to compare and contrast the perspectives of two entities, it’s time to think about the experience of considering multiple perspectives. Consider the following questions and capture your responses in the text field below.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Meet with your peers

(~20 minutes)

Get together with a peer group to share your responses to the 4 Ways of Seeing exercise and some of the insights you gained. After each person shares their responses and insights, discuss the following questions as a group:

- What have you gained from considering different perspectives?

- Think about the different types of questions considered. How might different types of questions contribute to deeper insights?

- In what ways do you anticipate using 4 Ways of Seeing in your daily work?

A personal reflection

(~5 minutes)

A slightly different use for the 4 Ways of Seeing technique is applying it to understand, contrast, and compare your own perspective and that of another person or group you need to work with. The goal is to help you identify ways to close the gaps between your perspective and theirs to improve your ability to align and work more effectively.

Similar to what you’ve done previously, you create four quadrants. And label them as follows:

|

HOW YOU SEE YOURSELF |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

HOW YOU SEE THEM |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

HOW THEY SEE THEMSELVES |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

HOW THEY SEE YOU |

|---|

| Enter text here |

You can fill in these quadrants for yourself and the other group. Then consider these key questions:

- How much of what you’ve written is based upon assumptions as opposed to real knowledge?

- How can you close the gaps between the way you see the situation, and how the other group sees it?

- What opportunities do you see for working together more effectively with the other entity, despite the differences in perspective?

If you prefer, you can watch this short video for guidance on how to use 4 ways as a personal reflection tool.

Ask a mentor

(~10 - 15 minutes)

Mentors have the wisdom of experience and can help you expand your thinking.

Your next challenge is this:

Identify a mentor or other leader you respect. Ask them to share with you:

- How they consider multiple perspective in their daily work

- Some tips for incorporating perspective-taking into your day-to-day activities

Jot those tips in a notebook for future reference.

Put your perspective-taking skills to work

(~10 minutes)

Now, it’s time to try out considering multiple perspectives in your work.

In this activity, you will reflect on an experience at work, school, or your personal life.

Here’s what to do:

- Identify an issue or topic that you want to understand more deeply, and the two perspective/groups involved in the issue that you are familiar with.

- Once you’ve identified the topic and the perspectives at play, complete the four quadrants chart below to practice considering multiple perspectives.

Group A:

|

How Group A views itself: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

Group B:

|

How Group A views Group B: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

How Group B views itself: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

How Group B views Group A: |

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Use additional scenarios to gain more practice with the 4 Ways of Seeing approach.

Alternative Scenarios:

BRIGADE DISCORD

You are recently given command of a Brigade. Over the past few weeks of getting to know your staff, you have noticed that your XO and S2 are constantly butting heads. They are not openly hostile to each other, but they seem to always come down on different sides of any issue, and to disagree about the nature of a problem and how to best address it.

Recently, you asked your XO and S2 to run training exercises for your brigade based on new intelligence your S2 has received. You’ve asked them to share responsibilities in terms of leading and evaluating the training.

The two can’t agree on the best way to train the brigade with the new intelligence. The XO thinks the brigade should just receive a briefing with the intelligence and check the box as complete. He said the staff aren’t babies and they need to suck it up and read the 72 page report. The S2 believes that this approach is unengaging, unlikely to help the staff apply what they’ve learned, and insufficient. She wants to take a more active, scenario-based approach to the training. The XO thinks this will be a waste of time and has shut down on the S2, not cooperating on the alternative training approach. Their lack of cooperation is apparent to everyone.

You want greater collaboration across the staff, and how the XO and S2 deal with each other is getting in the way of that goal. You decide to use the 4 Ways of Seeing exercise to better understand where each person is coming from, and to think about how to manage the situation.

BRAZILIAN RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION

Excerpt from New York Times: Nov. 18, 2019

RIO DE JANEIRO —

The Amazon rainforest in Brazil lost an area about 12 times the size of New York City from August 2018 through July of this year, according to government data released Monday, which shows that deforestation in the biome has shot up significantly since the election of President Jair Bolsonaro.

The 3,769 square miles of forest cover lost during that period represents a 30 percent increase from the previous year and the highest net loss since 2008.

The new deforestation figures, released by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, provide the clearest evidence to date that deforestation in the Amazon is on a solidly upward trend on Mr. Bolsonaro’s watch.

Mr. Bolsonaro, who has long argued that conservation policies stymie economic development, has been disdainful of the environmental measures that reduced the Amazon deforestation rate between 2004 and 2012. His government has weakened enforcement of environmental laws by cutting funding and personnel at key government agencies, and it has scaled back efforts to fight illegal logging, mining and ranching.

Environmental activists said Monday’s announcement, while not unexpected, was deeply concerning for the Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest.

“This figure is the direct result of the strategy implemented by Bolsonaro to dismantle the environment ministry, prevent the enforcement of laws, shelve plans previous governments made to curb deforestation and empower, through rhetoric, those who commit environmental crimes,” Climate Observatory, a Brazilian environmental group, said in a statement.

“In a break with what occurred in previous years during which the rate rose, this time the government did not announce any credible measures to reverse the trend,” it said.

Mr. Bolsonaro’s approach to the environment — and the Amazon in particular — came under sharp scrutiny in August as a rash of forest fires, most attributed to humans clearing land, consumed large swaths of the biome. Facing outrage from European leaders and threats of an international boycott of Brazilian exports, the government deployed the military to help contain the blazes.

But the Bolsonaro administration has continued to weaken the agencies tasked with enforcing environmental laws and regulations. And it maintains that industries such as mining and agriculture should have broader access to protected lands, including Indigenous reserves.

The environment minister, Ricardo Salles, said on Monday that the rise in deforestation had started well before Mr. Bolsonaro’s government came to power in January.

He added that the “unlawful economy” in the Amazon, where illegal logging and mining is rife, was largely to blame. “We need strategies to contain that,” Mr. Salles said during a presentation to journalists. He did not outline a detailed plan to combat the trend.

Experts say the damage unfolding in several Brazilian states is causing irreparable harm to the Amazon. The forest is often called the Earth’s “lungs” for its vast capacity to release oxygen and store carbon dioxide, a major cause of global warming. Some experts fear that so much forest will be lost that the area will transform into savanna, which cannot store as much carbon.

“We must remember that the Amazon has been undergoing deforestation for decades,” Oyvind Eggen, the secretary general of the Rainforest Foundation Norway, said in a statement. “We are approaching a potential tipping point, where large parts of the forest will be so damaged that it collapses.”

Gilberto Câmara, the secretariat director of the Group on Earth Observations, a coalition of governments and researchers that share and analyze data to shape public policy, said the growing destruction of the Amazon is doing tremendous damage to Brazil’s image and economic prospects.

“The decision of foreign investors to bring resources to Brazil is increasingly contingent on compliance and rules regarding sustainability,” said Mr. Câmara, a former director of the National Institute for Space Research, the Brazilian agency that tracks deforestation by studying satellite images.

“From the point of view of future generations,” he said, “the loss of biodiversity and the rise of emissions are huge setbacks that will have enormous consequences over the next 10, 15 years and beyond.”

Mr. Bolsonaro and several senior government officials have been dismissive of international criticism over deforestation, arguing that Brazil has done more than many other countries to conserve its forests.

Earlier this year, shortly before the Amazon fires made international headlines, Mr. Bolsonaro said that protecting the environment mattered only to vegans. In August, when Germany said it would devote funds to conservation efforts in Brazil, he suggested that Chancellor Angela Merkel “take that money and use it to reforest Germany” instead.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/18/world/americas/brazil-amazon-deforestation.html

CHINA VERSUS TAIWAN

Taiwan says there may be ‘military conflict’ if China economic slowdown gets ‘serious’

Excerpt from Reuters: Nov. 7, 2019

KEY POINTS:

As Taiwan’s presidential elections approach in January, China has stepped up a campaign to “reunify” with what it considers a wayward province, wooing away the island’s few diplomatic allies and flying regular bomber patrols around it.

China’s economy, though still growing, is expected to slow to a near 30-year low this year, underscoring a stiff challenge for Beijing in stepping up stimulus to keep up growth that has been fundamental to the Communist Party’s political legitimacy.

STORY:

Beijing could resort to military conflict with self-ruled Taiwan to divert domestic pressure if a slowdown in the world’s second largest economy amid trade war threatens the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party, the island’s foreign minister has said.

As Taiwan’s presidential elections approach in January, China has stepped up a campaign to “reunify” with what it considers a wayward province, wooing away the island’s few diplomatic allies and flying regular bomber patrols around it.

In an interview with Reuters, Taiwan’s Foreign Minister Joseph Wu drew attention to China’s slowing economy amid its bitter trade war with the United States.

“If the internal stability is a very serious issue, or economic slowdown has become a very serious issue for the top leaders to deal with, that is the occasion that we need to be very careful,” Wu said on Wednesday.

“We need to prepare ourselves for the worst situation to come ... military conflict.”

China’s economy, though still growing, is expected to slow to a near 30-year low this year, underscoring a stiff challenge for Beijing in stepping up stimulus to keep up growth that has been fundamental to the Communist Party’s political legitimacy.

Wu said the economic situation in China was “OK” at the moment but urged other countries to watch for what he saw as problems there, such as unemployment and popular discontent.

“Perhaps Xi Jinping himself is called into question of his legitimacy, by not being able to keep the Chinese economy growing,” Wu said, referring to China’s president.

“This is a factor that might cause the Chinese leaders to decide to take an external action to divert domestic attention.”

China’s growing military aggression in the region has become a “very serious” source of tension, Wu said, affecting many countries, but added that Taiwan was trying whatever it could to ensure peace across the Strait.

“We certainly hope that Taiwan and China could live peacefully together, but we also see there are problems caused by China, and we will try to deal with it.”

Taiwan has lost seven diplomatic allies to China since President Tsai Ing-wen took office in 2016. Beijing suspects Tsai of pushing for the island’s formal independence, which Xi has warned would lead to a “grave disaster”.

Tsai has repeatedly said she will not change the status quo.

‘Most difficult job’

Months-long anti-government protests in Hong Kong have provided a lesson for Taiwan, said Wu, who has been a vocal supporter of democracy in the Asian financial hub.

The protests in the former British colony have posed the biggest populist challenge to Xi since he came to power in 2012.

“People here understand that there’s something wrong (with)the way the ‘one country, two systems’ model is run in Hong Kong...Taiwan people don’t like to be in the same situation,” Wu said.

Beijing has repeatedly proposed to rule Taiwan under a “one country, two systems” formula similar to that prevailing in Hong Kong, guaranteeing certain freedoms, but the island has shown no interest in being run by autocratic China.

Wu vowed to help Hong Kong people “striving for freedom and democracy”, promising that, if needed, Taiwan would “provide some assistance to them on an individual basis”.

He did not elaborate, except for saying Taiwan would not intervene in the protests.

Wu, who described his post as “the most difficult ministerial job in the world,” has seen five countries switch diplomatic ties to China, whose complaints also drove many global firms to alter their descriptions of Taiwan.

“Acknowledging that Taiwan is part of China in exchange for some diplomatic space - I believe such a condition is unacceptable,” Wu said. “Taiwan’s diplomacy shouldn’t be outsourced to China.”

China could snatch more of Taiwan’s remaining 15 diplomatic allies, Wu added, in a bid to influence the elections, at which Tsai is seeking re-election.

“We are working closely with the United States and other like-minded countries to make sure the switch of diplomatic relations doesn’t happen again.”

Washington has no formal ties with Taiwan but is bound by law to help defend it.

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/07/taiwan-warns-of-military-conflict-if-china-economic-slowdown-is-serious.html

Premortem

Welcome to The Premortem

(~3 minutes)

This exercise will give you practice in anticipating how a project plan might go wrong. Using the Premortem technique, you will imagine a plan has been implemented and has failed. You will consider the factors that contributed to the undesirable outcome, along with ways to mitigate or manage those factors.

What’s the value of the Premortem?

Source: Henry Martin, New Yorker, April 23, 1979

As teams develop plans and get closer to a decision, they usually discard options and commit to a particular course of action. In doing so, teams become invested in their plan. They often over-estimate its chance of success and downplay the possibility that it will have setbacks or fail entirely. The plan they have chosen may be an excellent option—but no plan is perfect. Nonetheless, as the team members invest time and effort in moving the plan forward, they often become less likely to surface questions and concerns. This is particularly true if they are newer or more junior members of the team.

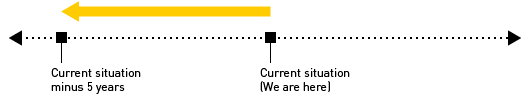

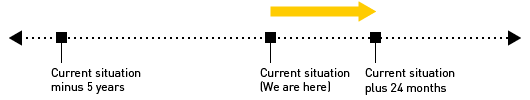

The Premortem is a technique designed to combat over-confidence and groupthink about a plan through a shift in perspective called “prospective hindsight.” Prospective hindsight involves jumping ahead in time, visualizing a particular outcome, and then looking back to consider how that outcome might have occurred. Shifting perspective in this way helps people identify risks, vulnerabilities, assumptions, and gaps in their thinking that they may otherwise miss.

Most Army officers are familiar with post-mortems, debriefs, or “hotwashes” that are conducted after a plan has been implement and used to capture lessons learned. In contrast, the Premortem is used once the team has developed a plan, but prior to project/mission launch. It provides a forum for the team to consider what can get in the way of success, including potential pitfalls and risks that need to be managed. It can help the team overcome blind spots and over-confidence and reduce the chances of unanticipated surprises.

To learn more about the Premortem see this article.

Reflect: Where might a Premortem have helped?

(~5 minutes)

|

Take a moment to reflect on the prompt below. Capture your responses in the text field below.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Now that you’ve finished your reflection, watch this video to see what Nobel Prize winner Dr. Daniel Kahneman says about the value of the Premortem technique.

Get warmed up:

(~5 - 10 minutes)

It’s time to warm up with a simple example and practice of the Premortem technique. For illustrative purposes, let’s say you are planning a party to celebrate your parents’ upcoming retirement. You decide to conduct a Premortem on your party plan to ensure it is successful.

Here's what you would do:

Step 1. Fast forward and envision a failure: Imagine that you are looking into a crystal ball and watching the retirement party unfold, and what you see is beyond disappointing. By all accounts, the celebration is a complete disaster. Your parents are unhappy, you feel humiliated, and you highly doubt your parents’ friends will ever RSVP for another party you throw!

Step 2. List every possible cause of failure you can imagine: Now that you’ve envisioned the disappointing scenario, the next step is to consider all the reasons the party unfolded the way it did. As you use your prospective hindsight skills, you determine that the following reasons contributed to the failed event:

- The food arrived late and was cold.

- The band never showed up.

- Thunderstorms rolled in (and the party was intended to be outdoors).

- 3 of your parents’ friends became sick from apparent food-poisoning.

|

What other causes for failure can you think of? Enter your ideas in the text box below. |

|---|

| Enter text here |

Step 3: Prioritize and determine how to mitigate: Now that you have identified several possible reasons for the party’s failure, pick the reasons that concern you the most. Then, consider what actions you might take to reduce the likelihood of each of those reasons becoming a reality. Here’s an example of what you might come up with:

| Reasons for the plan’s failure | How you might have reduced the likelihood of this happening |

|---|---|

| The food arrived late and was cold. |

|

| The band never showed up. |

|

| Thunderstorms rolled in (and the party was intended to be outdoors). |

|

What other reasons for failure can you think of? And how can you reduce their likelihood of happening?

Add any additional causes and how you might reduce their likelihood of ruining your parents’ retirement celebration in the text field below.

| Reasons for the plan’s failure | How you might have reduced the likelihood of this happening | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

Take the challenge: Use the Premortem on a plan with greater complexity

(~5 - 10 minutes)

Now that you’ve warmed up with a simple example, your challenge is to try out the Premortem on a more complex plan.

Consider a Current Plan

Take a moment to reflect on a plan that has some complexity—perhaps it has multiple lines of effort, coordination across multiple groups, or complicated timing (or all of these). The plan you choose to work with should be one that is close to being launched, and one that you have been directly involved with, in collaboration with others. It could be a plan you have co-developed with your unit, your class, your co-workers, your neighborhood or faith community, or your friends and family. Once you have identified a plan, capture a basic outline of that plan in the text field below for reference.

| Enter text here |

Fast Forward & Imagine a Fiasco

With your plan in mind, the next step is to fast-forward to the future. Imagine that several months have passed since launching the plan – and by all accounts, it has been a complete failure. [Note: Imagining a “fiasco” or a “complete failure” may seem extreme. Yet without thinking in those terms, it can be tempting to imagine only minor things that went wrong. It can limit our thinking and cause us to miss important considerations or factors that can be mitigated.]

Those involved in the plan (your peers, your Commanders, your community collaborators, your family members) are barely talking to each other. They are all unhappy with how things turned out. Every time someone alludes to what happened, the discomfort and disappointment surrounding it are palpable.

Consider the Causes of the Failure

Now that you’ve envisioned this unfortunate future state, take 2-3 minutes to capture possible reasons the plan turned out so poorly. Some of the categories you might consider could be:

- Stakeholders

- Events

- Timing

- Environment

- Communications

- Personalities

- Equipment

- Human Error

As you think about reasons for this failure, be as concrete, specific, and realistic as possible. Capture as many as you can think of in the text field below.

| Enter text here |

Prioritize

Now that you’ve captured possible reasons why the plan has failed, pick the top three reasons that strike you as most concerning and/or most likely to happen.

Mitigation Plan

To reduce the likelihood that these factors contribute to the demise of your team’s plan – or to avoid them altogether – what actions might you take to address them? Capture your ideas for how to mitigate the issues you’ve identified in the text field below.

| Enter text here |

Reflect on the exercise

(~5 minutes)

Now that you’ve had a chance to practice the basic components of Premortem, it’s time to think about your experience of doing so. Consider the following questions and capture your responses in the text field below.

- What did you learn?

- What was hard about it?

- In what situations might you use the Premortem in the future?

- In what ways can you envision this technique being more powerful when conducted as a team?

Enter your reflections in the text field:

| Enter text here |

Put the Premortem to work: Use with your team

(~10 minutes)

Although the exercise you engaged in here gave you practice as an individual, the greatest benefits of the Premortem come from using the technique as a team. Each individual on a team has a unique set of experiences and mental models they bring. The Premortem leverages a team’s collective experiences and perspectives and reduces the illusion of consensus by creating a space where team members can actively surface concerns and potential pitfalls in a plan.

Before your team launches its next plan, use the Premortem to proactively identify where the plan could fail. Follow these steps:

- Envision a failure. Start by looking into the future and seeing that the plan is a complete failure.

- Consider the reasons for failure. Ask everyone to take 2-3 minutes to jot down all the reasons the plan was a disaster.

- Share and capture reasons for failure. Go round robin, taking turns describing the causes of the plan’s failure, with everyone in the room sharing one at a time. Capture the causes for failure on a whiteboard or flipchart for a shared visual reference. It is likely that some of the potential causes will be identified by more than one person. Capture this consensus by putting check marks by those items.

- Select top concerns. Once everyone has shared their reasons, choose the top 3-5 items of concern.

- Determine mitigation strategies. Work together to develop ways to avoid or mitigate those issues when/if they occur.

Reflect.

After you’ve done the Premortem with your team, reflect on the exercise either individually or with a peer. Consider the following prompts and capture what you learned in the text field below or in your notebook.

- How did the Premortem benefit your team and/or your plan?

- How was the Premortem different from other risk identification and/or risk mitigation approaches you have used before?

- How did use of the Premortem change the dynamic of your team?

- How did individuals who tend to be quiet and/or less critical of plans in a group setting behave in the context of the Premortem? For example, did you hear certain individuals raise concerns that they may otherwise not have?

| Enter text here |

Revisit

Periodically revisit your list of concerns to re-sensitize your team to problems that might be emerging as you carry out the plan.

If you’d like to print a job aid to guide you in your Premortem exercise, you can find a two-page overview from the Red Team Handbook here (Created by the University of Foreign Military & Cultural Studies (UFMCS)

Defining the Fundamental Problem

Welcome to Defining the Fundamental Problem

(~3 minutes)

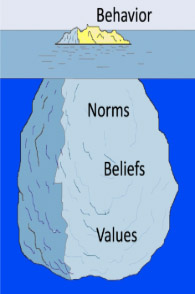

This exercise will give you practice in differentiating between the symptoms generated by a problem versus the underlying problem itself. When managing complex problems, we often do not recognize that the immediate issue or concern we encounter (i.e., the “squeaky wheel”) is actually a symptom of a larger or deeper systemic issue. We may get fixated on addressing the symptoms instead of identifying and managing the larger underlying problem.

Why does identifying the fundamental problem matter?

Underlying problems often generate symptoms that appear to require immediate attention. Responding to symptoms with a fast, short-term solution may yield quick results and have short-term benefits. And in some situations, quick response may be necessary and appropriate to prevent or slow further damage. However, when underlying problems or root causes are not addressed (or even recognized), symptoms eventually reoccur. Failure to identify and address the fundamental problem and its root cause may cause it to become more serious over time. Peter Senge (The Fifth Discipline) refers to the tendency to address symptoms rather than diagnosing and treating the underlying issue as “Shifting the Burden.”

For a simple example of responding to symptoms rather than identifying and addressing the underlying problem -

RESPONDING TO SYMPTOMS VS. THE FUNDAMENTAL PROBLEM: AN EXAMPLE

To bring this phenomenon to life, let’s consider a simple example.

Let’s say you have a headache today and you take aspirin to treat it. The headache will likely dissipate from the aspirin, and after it does, you may forget you even had a headache. If you get a headache in a couple of days, you may simply take another aspirin, since that worked before. You might start keeping aspirin with you, and soon you are taking one every time you get a headache. But what if the headache is a symptom of a more fundamental problem? Taking the aspirin every time you have a headache doesn’t do anything about the actual reason for your headaches or give you a way to adjust your health-related behaviors so you can avoid headaches altogether.

If you were to investigate reasons for headaches, it might lead you to consider the possibility that there are underlying issues that could account for the symptoms you are experiencing. For example, the underlying cause of the headaches might be your diet, insufficient water consumption, lack of sleep, or allergies. If you solely address the symptom by treating the headaches with aspirin, you may end up making the problem worse. For example, you may begin to experience digestive issues and stomach pain, in addition to the headaches. But if you instead address the fundamental problem(s), you have a greater chance of eliminating the headaches altogether. While addressing the underlying problem (diet, water consumption, sleep) may take longer and require more effort through behavior modification, you can expect a longer-term and more sustainable impact on your health.

Reflect: When have you treated symptoms versus addressing an underlying problem?

(~5 minutes)

|

Take a moment to reflect on the prompts below. Capture your responses in the text field below.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Learn: What clues indicate an underlying problem?

Four clues can help signal when you may be focused on responding to symptoms rather than identifying and addressing an underlying problem. They include the following:

- An issue you have addressed re-emerges.

- The issue worsens – or takes a different shape – over time.

- Additional problems related to the issue emerge.

- There is a sense that nothing you do seems to make a difference in any sustained way.

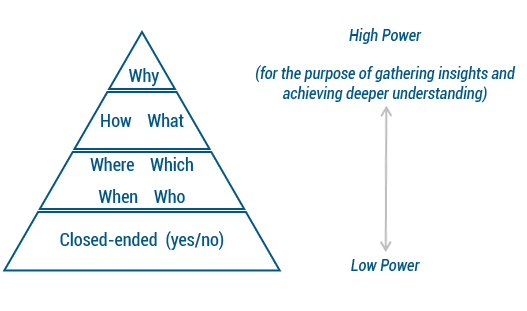

Defining the issues or “symptoms” is a good place to start. However, rather than moving directly to a solution or “treatment,” it is important to take the time to examine whether there’s a larger underlying problem that is producing the symptoms. Posing questions that enable you to get progressively deeper information about the symptoms will allow you to grasp the root causes and/or fundamental problem more fully, and to develop solutions that are more likely to be responsive and effective.

Tips for identifying root cause

(~3 minutes)

One of the challenges of distinguishing symptoms from underlying problems is that we can simply lose sight of the need to identify and deal with the underlying problem. Sometimes the symptoms are significant and require action. As we work to deal with symptoms, we “can’t see the forest for the trees.” Unfortunately, in addressing symptoms only, we may actually make the underlying problem worse.

Here are a few tips to help:

- It can be helpful to begin by listing all the ways the issue is showing up across time and various contexts. Doing so allows you to think about whether there are patterns and commonalities that point toward an underlying problem.

- It can help to consider all the potential causes of the issue you’re experiencing. What factors might be contributing to the issue? And which ones can you control or influence?

- Consider the actions you have taken to deal with the issue up to this point. How has the situation changed (if at all)? By observing what happens in response to actions or interventions you take (“action learning”), you can uncover useful information about the underlying problem(s) and root causes.

- It can help to simply consider the possibility that the issue you are dealing with might be a symptom of a deeper, systemic problem. Being cognizant of this possibility can prompt you to ask questions to identify the root causes or underlying problem.

As with any skill, practice and reflection will enhance your ability to understand a situation or problem more deeply.

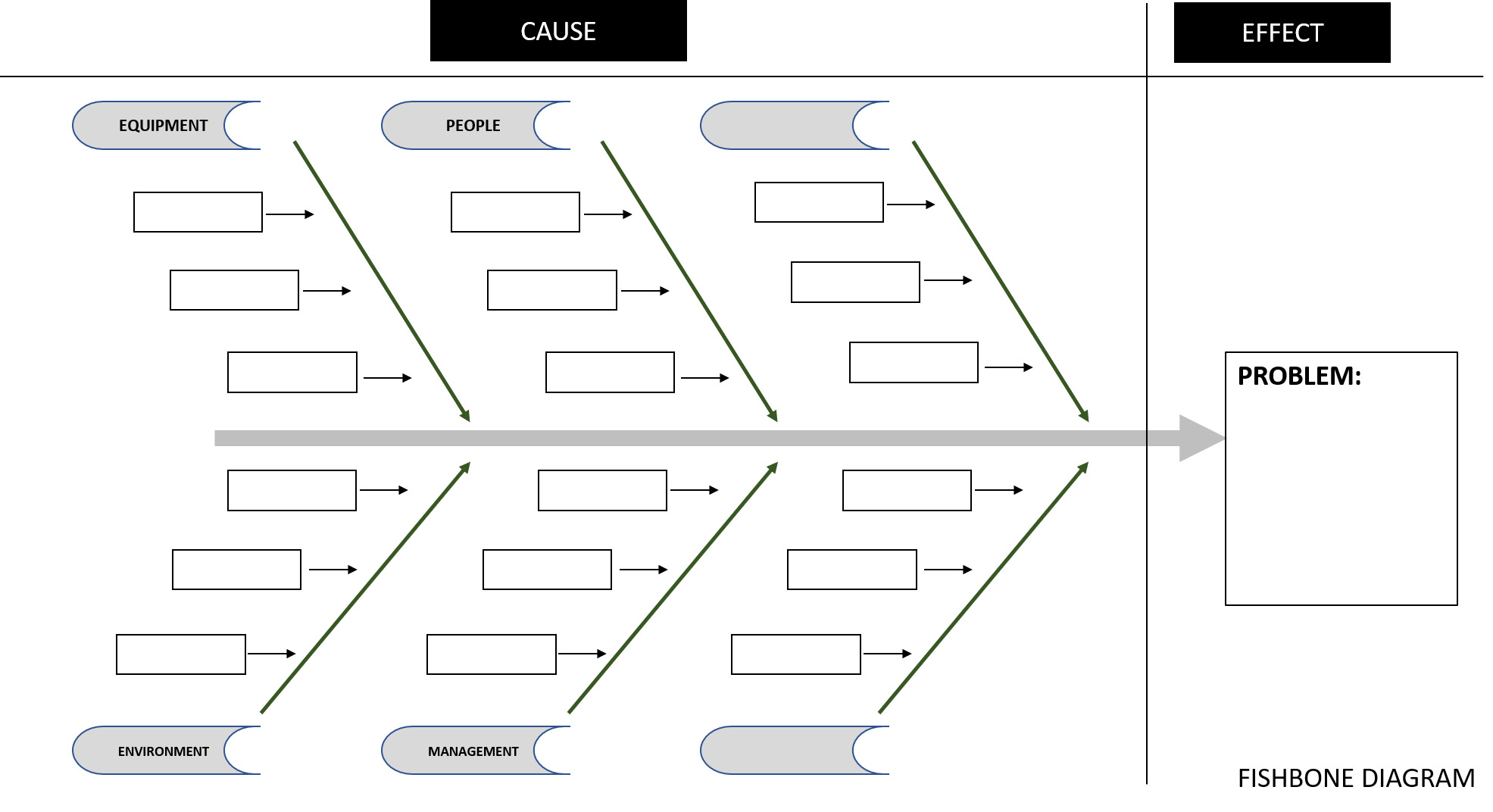

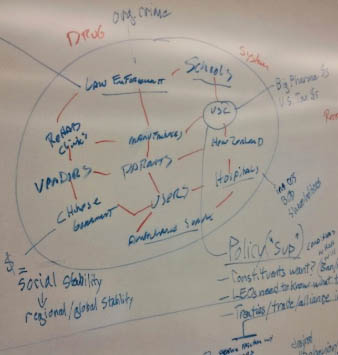

The fishbone diagram: A tool to identify root cause

(~5 minutes)

A fishbone diagram is a template to guide you through all the potential factors that may be causing a given problem. It’s called a fishbone diagram because it resembles a fishbone, with the problem resembling the ‘head’, and the various potential causes resembling the ‘spine’ of the fish.

Watch this video for an introduction to the fishbone diagram.

Steps to use this diagram:

- List the symptoms you are noticing in the situation.

- Define the problem that accounts for the symptoms you are seeing and fill it in on the right.

- Brainstorm all of the possible causes of the problem for each category listed.

- It is important that you don’t stop here. Once you have your initial diagram, probe further. Ask yourself ‘why’ for each cause you identify until you believe you have uncovered the true root cause. [To do this, you can use the “5 Whys” technique. Click here to learn more.]

The end result is that you have potential causes of your problem identified, and you can take action to validate the root cause and address it.

Click here to download a blank version of the fishbone diagram.

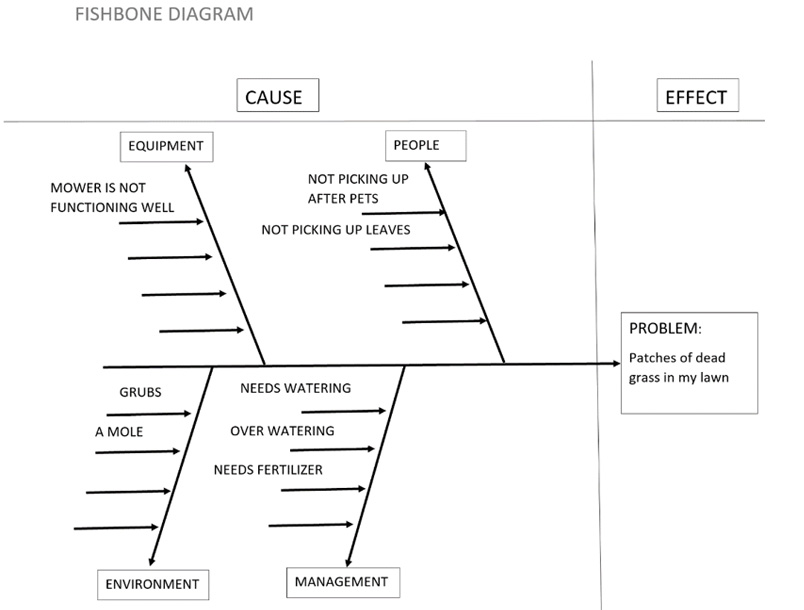

An Example: Lawn Troubles

(~5 minutes)

Imagine that you just moved into a new house, and you’ve made it a goal to have the best lawn on the block. The lawn currently has large patches of dead grass. At first, you are tempted to jump straight to buying some sections of sod to fully replace the dead grass. Instead, you decide to take a step back and think about what might be causing the dead grass before you jump to a solution.

Using the fishbone diagram, you brainstorm possible causes for the dead grass in your lawn.

Here is the result:

After working through this analysis and investigating the feasibility of some of these causes, you conclude that the most likely root cause of your patchy lawn is a lack of watering.

Why?

You have found no evidence of pest infestation. And you’ve been watching to see if there are neighbors not picking up after their pets. There’s no evidence of that going on, either. And the patchiness of the spots in the lawn do not seem to point to an equipment issue because the damage is inconsistent.

After talking with the previous owner, you learn that they have not been regularly watering the lawn and this has been the hottest year on record. Additionally, the areas with the dead lawn are areas that receive little to no shade. You make a plan to reseed the lawn and set up a regular watering schedule as your approach to meet your goals with your lawn.

Keep in mind that when using a fishbone diagram, you may not have all of the information readily available to determine the root cause of the problem. You might need to go investigate further. But, you can use this approach to ensure you are thinking rigorously about the problem and not jumping to conclusions. It can also help you identify what additional question you still need to answer to validate the root cause of your problem.

Take the challenge

(~10 - 15 minutes)

It’s time to practice the skill of identifying the underlying problem. Download and complete the fishbone diagram template to help you identify the root cause. Or you can draw a fishbone diagram in your journal using the previous example as a model.

Your challenge is this

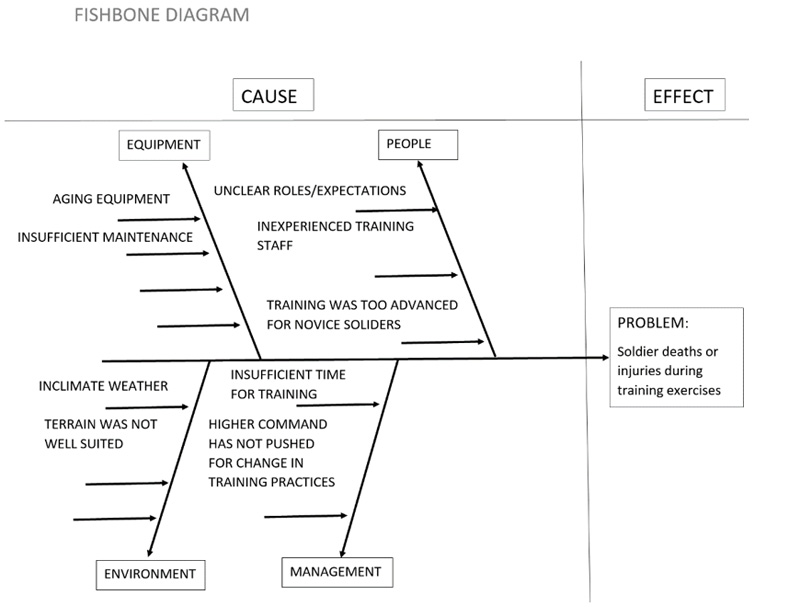

You will read through a set of news clips and reports about Army training issues. When you have read through the clips, complete your fishbone diagram by defining the underlying problem, exploring potential root causes, and considering possible interventions for addressing the underlying problem.

In 2019, Army Spc. Nicholas DiMona III died during a live-fire exercise in Alaska that some fellow soldiers said lacked control of the maneuver and felt rushed, according to witness statements obtained by Army Times. Soldiers also said that nighttime targets were not always clearly marked as they shot without tracer rounds, the roles of safety and training personnel were mixed and there was confusion among soldiers regarding the shifting and lifting of gunfire. (See this news report for more information).

A vehicle rollover at Fort Polk, Louisiana’s Joint Readiness Training Center left one civil affairs soldier dead and a dozen others injured, according to a release from 1st Special Forces Command. The accident involved a rolled Humvee, Fort Polk spokeswoman Kim Reischling confirmed to Army Times. A Marine was killed in a similar incident at Camp Pendleton, California, on May 9. (See this news report for more information).

The 1st Cavalry Division has moved to oust three junior leaders and ordered reforms to its driver's training program after a 20-year-old infantryman was killed last year in a rollover accident involving a Bradley Fighting Vehicle at Camp Humphreys. The Fort Hood Army division acted after finding that Spc. Nicholas Panipinto had no license or classroom instruction and had received only six hours of hands-on training when he died during a Nov. 6 road test of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle. Two other soldiers were injured. (See this news report for more information).

Two special operations soldiers were killed and three were injured in an aircraft mishap during an Army Special Operations Command training exercise near Coronado, California, according to an Army Special Operations Command spokesperson. The incident occurred when the troops’ Blackhawk helicopter crashed on San Clemente Island. See this news report for more information.

This incident comes after nine service members were killed in an amphibious assault vehicle while returning from a training raid at San Clemente Island. Eight of 15 Marines on board the AAV and one sailor died in that accident. (See this news report for more information).

In fiscal year 2019, the Army suffered a total of 55 Class A mishaps and 61 Class B mishaps, 28 soldier casualties and $362 million in damaged or lost equipment not related to losses in combat. Those mishaps were caused by a combination of increased training with heavy equipment, and the need to inculcate among young troops fundamental skills that have lapsed in recent years, Army Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville told the House Armed Services Committee. (See this news report for more information).

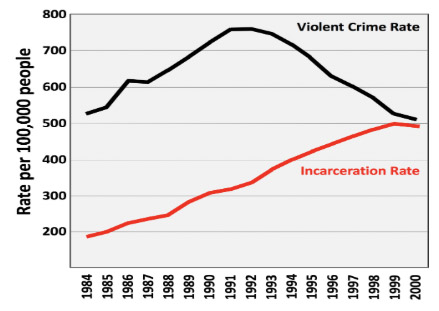

According to a report by the Congressional Research Service, between 2006 and 2018 a staggering 32 percent of active-duty military deaths were the result of training accidents.

During that same time period, only 16 percent of service members were killed in action. And in 2017 alone, nearly four times as many service members died in training accidents than were killed in action. Serious steps need to be taken to prevent these tragedies from continuing.

Complete your fishbone diagram:

Now that you have read the news reports, follow these steps:

- List the ‘symptoms’ you have identified from these articles. Enter those symptoms in this field.

- Define the underlying problem in these articles that accounts for the symptoms you identified. Capture your response in your fishbone diagram in the problem section. (Access blank fishbone diagram here.)

- Next, reflect on the pattern of issues described in the reports, and consider some possible causes for the problem. Consider causes relating to people, equipment, environment, and management. Enter your potential causes in the spine section of your fishbone diagram.

- Now that you have entered some potential causes to the problem in your diagram, what are some ‘why’ questions you can ask to get as close to the root cause as possible?

Capture your ‘why’ questions here: - Select three root causes from your diagram that you think are most probable. What might be potential solutions to those root causes you identified? Fill in your ideas in the table below.

|

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

|

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

| Root Cause | Potential Solution | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

Now that you have explored the root cause of the situation, take a moment to view and compare your responses with an expert’s fishbone diagram, ‘why’ questions, and potential solutions. As you read the expert’s response, consider:

- What similarities exist with your responses and the expert’s response?

- Did the expert note anything you did not think of?

- Did you think of something the expert did not?

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE

Symptoms identified:

- Failed training exercises

- Solider deaths and injuries

- Overturned vehicles

- Equipment malfunctions

Possible questions to help pinpoint the root cause:

- Why are roles and expectations unclear during training exercises?

- Why are training staff inexperienced?

- Why are novice soldiers in exercises that are too advanced for them?

- Why is there insufficient time available for training? How is time being allocated to other activities, relative to training?

- Why were training exercises run in conditions that may not have been ideal?

- If the equipment is not sufficiently maintained, why is it not sufficiently maintained? Is it a matter of time? Skill? Oversight?

- What is preventing higher command from pushing for investigation into training practices? Are they aware of the issues? Do they believe the issues are lower priority, relative to other ones?

Solutions or Interventions:

The appropriate solutions to the problem will be informed by identification of the root causes.

The expert selected three potential root causes with solutions to serve as examples for you. Keep in mind, you would need to validate your root causes through investigation before deciding on a solution.

| Root Cause | Potential Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient equipment maintenance | Revamping maintenance personnel selection practices, in tandem with offering a training program to close knowledge and skill gaps |

| Unclear roles/expectations | Clearly defined roles and expectations at start of training |

| Insufficient time for training | Allocating a set number of training hours per month and holding everyone accountable for ensuring they take place |

Reflect on the exercise

(~5 minutes)

Now that you’ve had a chance to think about how symptoms can be indicative of a fundamental or underlying problem, it’s time to think about the exercise experience. Consider the following questions and capture your responses in the text field below.

|

|---|

| Enter text here |

Meet with your peers

(~20 minutes)

Get together with a peer group to share your responses to the Defining the Fundamental Problem exercise and some of the insights you gained. After each person shares their responses and insights, discuss the following questions as a group:

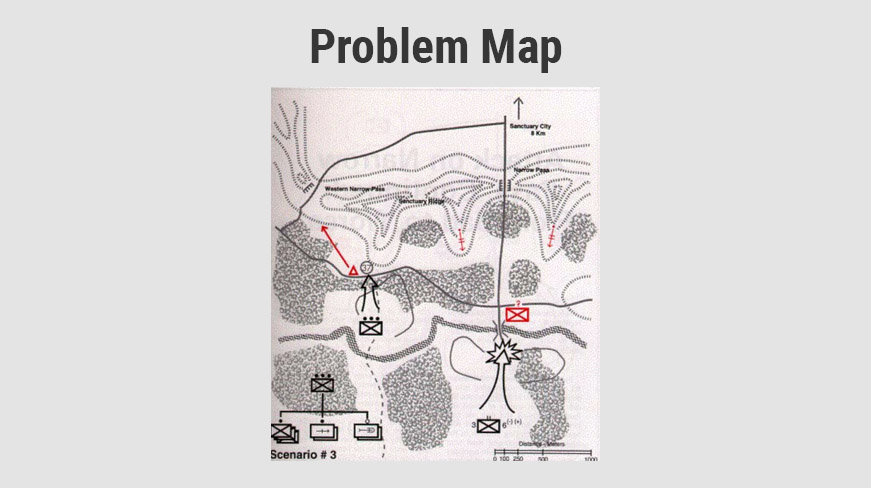

- What are some examples of symptoms with larger underlying problems that you – and members of your group - have encountered in your careers?