PRACTICAL GUIDANCE

GUIDANCE TO HELP IMPROVE YOUR SKILLS

Leadership Assessment Tools

Campbell Leadership Descriptor $

Description: Self-assessment designed to help individuals identify characteristics for successful leadership, recognize their strengths, and identify areas for improvement.

Access: http://www.ccl.org/leadership/assessments/CLDOverview.aspx

MSAF360 – The Army’s Multi-Source Assessment and Feedback

Description: A 360° (i.e., multi-source) survey that provides individuals with feedback on their leadership strengths and areas for improvement. (CAC login required)

Access: http://msaf.army.mil/LeadOn.aspx

Multifactor Leadership Description Questionnaire (MLQ) $

Description: A questionnaire assessment that measures leadership types. Considered the benchmark measure of transformational leadership.

Access: http://www.mindgarden.com/products/mlqc.htm

Profiles of Organizational Influence Strategies (POIS) $

Description: An assessment tool that measures how people use influence within their organizations.

Access: http://www.mindgarden.com/products/pois.htm

SKILLSCOPE® Team Feedback Assessment $

Description: A 360° (multi-source) assessment checklist that provides individuals with feedback on job-related skills necessary for effectiveness in a leadership role.

Access: http://solutions.ccl.org/SKILLSCOPE

Starter Phrases or Questions

Some example starter questions or phrases include the following:

- What do we know? What do we think we know? What do we need to know that we don’t know right now?

- What are we missing? What factors are we not accounting for?

- Let’s think about and discuss the strengths and limitations of this idea.

- What is the biggest question on your mind right now?

- Where does this idea fall short? Where is it most robust?

- Let’s think about how this assumption may (or may not be) valid; then let’s discuss.

- Help me understand your perspective better.

- What are the pros and cons for this idea/concept?

- Help me understand what I am missing. Where is my idea flawed?

- What are you puzzling most about right now?

- What connections or relationships are we missing?

- Everybody think of one drawback (or strength) of this idea/concept.

- How well does this model account for what we’re trying to understand? What is it missing?

- Where might we expand our research and learning?

- We’ve characterized this (phenomenon) as a problem about (X).

- Is this the right level?

- Should we be looking at a higher level? A lower level?

- You've observed this (phenomena). Why do you think it takes place?

- What are its possible causes?

- If the relationships are not cause/effect, are they still worth thinking about as probable associations?

- Should we be looking at a higher level? A lower level?

PRACTICAL GUIDANCE

Welcome to Practical Guidance

Explore the topics on the left to expand your understanding of complex problems and how to manage them.

The insights and guidance in this section are based on research conducted by the U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences.

Complex Problems: Some Basics

Operational Complexity: What Is It?

The Army faces operational environments that present enormous challenges including:

- Volatile and highly dynamic conditions

- Multiple players and factors that interact in complicated and unexpected ways

- Difficulty knowing the accuracy or completeness of available information and meaning that is often unclear

Among the operational settings Army Officers encounter are low-intensity conflict situations and problems that fall within a “gray zone,” marked by levels of complexity that challenge even experienced Army leaders.

The Nature of Complex Problems

Complex problems are inherently messy. They involve multiple components that are interconnected and that interact in unexpected ways. Important components of a problem and the relations among them may be difficult to discern and highly fluid. With complex problems, boundaries are unclear, cause-effect relationships are ambiguous, and outcomes are often unpredictable.

Listen to what COL (Ret.) Jim Greer has to say about recognizing complex problems:

(Recorded in 2017)

The volatility, uncertainty, and ambiguity of today’s operational environments add to their complexity and make solutions elusive.

Some examples of complex problems include climate change, global poverty, international drug markets, and terrorism.

One of the challenges of working in complex environments is that people often see complex problems and situations as simpler than they really are. The inclination to underestimate the complexity of problems is known as the reductive tendency. Underestimating complexity is a common response when factors are:

- Continuous rather than discrete – for example, currency inflation (continuous) vs membership in NATO (discrete)

- Dynamic rather than static – for example, territorial control in the Syrian conflict (dynamic) vs. territorial control governed by the Korea DMZ (static)

- Simultaneous rather than sequential – for example, information from social media (simultaneous) vs email (sequential)

- Interconnected rather than independent—for example, effects of weather and terrain on combat operations (interconnected) vs. the effects of terrain on troop strength (independent)

One approach people use to manage complexity is to reduce the problem down to smaller, fewer, and/or simpler components. They are also likely to hold onto this simplified understanding, even when confronted with information that suggests the situation is more complex than they think it is.

Listen to what LTG H.R. McMaster says about the tendency to over-simplify complexity.

(Recorded in 2017)

When leaders underestimate problem complexity, the plans and decisions they make may be ineffective and may lead to unexpected and adverse outcomes.

It is possible to overcome the tendency to oversimplify complexity. However, doing so requires skills developed through:

- Practice

- Experience

- Effort

Managing Complex Problems: Core Activities

Effectively managing complex problems requires leaders who are able to:

- Think holistically.

- Recognize connections and linkages.

- Anticipate the ripple effects of decisions.

- Visualize how situations might evolve into the future.

And, they need to do this advanced thinking in settings where volatility, uncertainty, and ambiguity are the norm.

Core Activities

Although the specifics of the operational setting obviously matter, skilled Army leaders consistently describe a set of core activities involved in effectively managing complex problems in operational settings. The core activities are presented in the graphic below. To learn more about each core activity, click on the activity.

Managing

Complex

Problems

Each of the core activities is essential to managing complex problems. Effectively managing complex problems means knowing how and when to engage in the core activities. The work is not a linear, step-by-step process. Instead, it is iterative, recursive, overlapping, and fluid.

Recognize Complexity

It is not always clear that you are dealing with a complex problem. People’s tendency to underestimate complexity is most likely to occur when they are faced with unfamiliar environments and/or problems. Often, complex problems appear fairly simple on the surface, particularly when you first encounter them. One of the challenges of appreciating the complexity you are dealing with is that people may find it difficult to let go of their initial, simplified view.

Problems that are not complex are well-defined. They have clear boundaries. Solving them may require significant time and effort, but it is possible to identify a solution and a clear path to it.

With complex problems, that isn’t the case. The very nature of the problem is typically unclear and difficult to define. Solutions are not obvious. For these reasons, they are often referred to as “wicked” problems.

Often, individuals, leaders, and organizations do not realize they are facing complex problems until they begin trying to address them. They find that solutions that seemed well-crafted do not have intended effects. There may be surprising outcomes or unintended consequences. These are all indicators that problems are not well-understood and may be more complex than originally thought.

Recognizing early on that a problem set is complex allows you to take the time and allocate the resources needed to understand it more completely. With a deeper, fuller understanding, the plans you develop are more likely to be effective.

"...[the] reductive tendency is an inevitable consequence of how people learn...Of necessity, when people are forming a new understanding or developing a new category, their knowledge is incomplete. How else could it be? People perceive, understand, and learn distinctions only through additional experience and thought. So, at any point in time, a person's understanding of anything that's at all complex, even domain experts' understandings, is bound to be simplifying at least in some respects."

-Feltovich et al., 2004, p.91

Here are some tips for recognizing complex problems. They are based on research by the U.S. Army Research Institute with experienced Army leaders. Asking these questions will help you reflect on the problem you are thinking about and begin to understand it more fully:

- Are multiple players involved?

- Are there critical time constraints?

- Is the problem changing rapidly?

- Is there a variety of factors at play – e.g., cultural, social, political, economic aspects?

- Are multiple – potentially competing – goals in the mix?

- Is the problem possibly a symptom of another, even larger problem set?

- Are second-and third-order effects (ripple effects) a possibility, depending on the course of action we take?

- Is the problem nested, or intertwined, with another problem or set of problems?

- Are there disagreements among experts about the nature of the problem and the appropriate solution?

Develop an Understanding of Complex Problems

Managing the volatility and complexity of complex operational environments requires Army leaders who can think both tactically and strategically, and have the advanced thinking skills that support:

- Developing a holistic view of multi-dimensional problems

- Identifying the systems and subsystems that make up the environment, in which complex problems are embedded

- Visualizing current and potential future states

- Identifying ways to shape the future to the benefit of U.S. and allied partners’ interests

The importance of building a comprehensive, in-depth understanding of the operational environment cannot be overstated. Plans and solutions based on quickly-formed, surface-level notions of the environment and the sets of problems within it may be ineffective. Worse, they may have unintended, adverse effects.

Here are some tips for developing your understanding of complex problems. They are based on research by the U.S. Army Research Institute with experienced Army leaders.

Think holistically about the problem. Expand the frame you are using by taking a step back--“zoom out.” Consider the problem set from this larger context that surrounds it. Think about what the problem is connected to and what those connections might mean. Use this holistic view of the problem to switch back and forth between the big picture and detailed thinking. See what each perspective can tell you about the other.

Use an approach such as Army Design Methodology (ADM). ADM is part of Army doctrine. It provides processes to define the problem and identify desired goals or outcomes before moving into problem solving and detailed planning. To understand how to bring ADM and more detailed planning together, see the Integrated Planning Handbook.

Think about thinking. Reflect on the perspectives, worldviews, and biases you bring to the team. To help you do this, consider using some of the tools and inventories that assess aspects of cognitive style, preferences for learning and information processing, personality type, and interaction styles. These tools can help increase your self-awareness about the way you typically think and approach problems.

Prepare for ambiguity. Complex problems are full of ambiguity and making sense of them can be confusing work. Teams manage that confusion and ambiguity better when they know to expect it and understand that it is normal. Rather than seeing moments of confusion and uncertainty as signs of trouble or failure, they can be the impetus for significant learning and novel insights.

Prepare your physical workspace. Arrange for a workspace and materials to work with that are conducive to collaborating and developing shared understanding. Optimal physical space would support:

- Independent work such as research and quiet reflection

- Group work such as discourse, discussion, and sharing ideas

- Individual and group visualization activities and access to shared content (e.g., whiteboards, wall space)

- Making a mess, using materials such as post-its, images, collages, and sketchpad

- Reconfigurable space that supports different work modes and team activities

- Face-to-face interaction during discussion (e.g., circular seating configuration)

Pose starter questions. Ask team members to generate all the questions they can think of regarding the current situation. Use those questions as a basis for reflection, team discussion, and information-gathering. Or, use a set of starter phrases or questions to seed the team’s initial discussions.

Seek a variety of sources. Intentionally seek information from a wide variety of sources that reflect different points of view (e.g., books, periodicals, news outlets, social media, and subject matter experts). Also, use different methods of inquiry (e.g., both qualitative and quantitative approaches).

Encourage a positive climate that supports discourse and lively debate. Energetic exchange of ideas is a key activity for teams to expand learning and achieve deeper understanding of complex problems. Commanders and other leaders play a critical role in creating a climate that encourages individuals to share and critique ideas freely. For more on the role of discourse, see The Power of Discourse..

Consider the following questions about how you may (or may not) be contributing to a climate of respectful, productive discourse:

- Do you encourage participation of all ranks and downplay the importance of hierarchy?

- Do you invite others to disagree with your ideas and question your assumptions?

- Do you actively seek out different perspectives?

- Do you use respectful tone and language in your critiques and disagreements?

- Are you engaged and listening actively when others are talking?

Use visualization tools and techniques. Working with visual representations allows many people to think differently and to have different kinds of insights. Visual tools will help you think more holistically, consider relationships among elements of the problem, and communicate your evolving understanding to other team members.

Listen to COL Paula Lodi describe the value of using visual techniques to understand complex problems.

(Recorded in 2017)

- Have on hand materials and tools that foster visual thinking such as:

- Whiteboards, flipcharts, post-its, markers, and pens

- Wall space where materials can be posted

- Materials such as sets of images, shapes, connectors, words, arrows that can supplement sketching activities (example toolkit)

- Cameras, laptops, projectors

- Use a variety of types of visual tools to explore the problem. Consider using techniques such as mindmaps, fishbone diagrams, or concept maps, but also simple tools (whiteboards, flipcharts, toolkits). Click here for some examples.

- Recognize the limitations of certain tools. PowerPoint and other software have important uses, but they can stifle critical thinking and creativity, and impede understanding of complex problems.

- Remind yourself and others that artistic talent is not a requirement for effective visualization. People sometimes feel intimidated about going to the whiteboard and drawing their ideas. Remind yourself and others that rough sketches can communicate important ideas. The point is not to create good art, but to use a visual language to achieve new insights.

Collaborate with Others

Complex problems by their very nature require teams (and often teams of teams) to develop a deep and comprehensive understanding of a problem set and how to address it. It is unlikely that any one person—including Commanders and Army leaders-- will have the full set of knowledge and advanced thinking skills needed to grasp the situation.

For that reason, teamwork skills and the ability to work collaboratively are essential to effective performance in complex operational settings.

Here are some tips for collaborating with others to manage complex problems. They are based on research by the U.S. Army Research Institute with experienced Army leaders.

Include people with diverse backgrounds and perspectives. Teams with little diversity of background or point of view have a much harder time understanding complex problems or developing innovative solutions. Bringing together individuals with different perspectives, backgrounds, knowledge, diverse thinking styles, and personality characteristics will increase the likelihood that new connections and insights will occur.

In addition, teams benefit when members have a mix of skills, attributes, and workstyles. Effective teams are likely to have at least some team members who are:

- Open minded, with room for new ideas

- Comfortable with ambiguity

- Creative and innovative

- Avid readers with an ability to digest and synthesize large amounts of information

- Skilled in research or investigation

- Willing to listen to others and respect differing points of view

- Willing to speak up and share their points of view

- Comfortable with and eager to have their own ideas critiqued

- Inquisitive, curious, and eager for knowledge

- Comfortable looking at a problem from different perspectives

- Adept at thinking and communicating ideas both verbally and visually

Make roles explicit. Teams are more effective when team members talk over the tasks and activities important for helping the team do its work, decide who will do what tasks, and figure out how to keep track of key tasks. The specific person doing the task is less important than making sure that it gets done. There isn’t any requirement for the same person to fill a specific function over time. Some of the tasks and activities to consider in assigning roles include:

- Capturing group discussion in text notes

- Capturing sketches and other graphics

- Thinking about metrics, and developing ways to test the insights the team develops

- Leading and/or monitoring the team’s work process and dynamics

- Playing devil’s advocate, including questioning the team’s assumptions

- Managing information on current operational constraints in order to evaluate the feasibility of proposed approaches or solutions

Consider the Commander’s role. In complex problem-framing and -solving activities, the Commander has a critical role in providing guidance and setting constraints for his/her staff. However, Commander involvement in day-to-day work of the team is rarely an option. Experienced Commanders have offered the following suggestions for thinking about how and when to be involved:

- What will the level and nature of my involvement be in the activity?

- What are the critical parts to be involved in? Where can I have the greatest impact?

- How do I want the team to communicate their logic and insights to me? How frequently? In what formats? (e.g., PowerPoint slides? A narrative description? A graphic? An email with bullet points? A combination of these formats?)

In parallel, the staff has an important role in determining when it’s critical to bring the Commander into their work.

Agree upon and monitor the team dynamic. Occasional reflection and discussion about how the team wants to operate, and how things are going supports good teamwork. Example topics for those discussions might include:

- Are there particular work processes and ways of working together that the team sees as most productive?

- Are certain types of interactions among team members particularly beneficial?

- Are there aspects of the team’s interactions that are getting in the way of its effectiveness?

Engaging team members as active participants in monitoring and adjusting how the team functions has ongoing benefits for how the team operates and the quality of its work.

Encourage productive conflict. Although interpersonal conflict (i.e., personal attacks) is harmful, conflict centered on ideas and work processes can be positive and productive. It can lead teams to clearer thinking and better solutions (see Lencioni’s Conflict Continuum). Examples of language that can spur productive conflict includes:

- “The point I made doesn’t seem to be resonating with you. Help us understand what you’re thinking.”

- “You seem to be disagreeing with that concept. Help us understand where our ideas aren’t aligning.”

- “Tell us why that idea doesn’t make sense from your perspective.”

Vet ideas by considering their strengths and weaknesses. Rather than classifying ideas as good or bad, acknowledge that all ideas or viewpoints have both good/useful and bad/not useful aspects. However “bad” an idea might seem, it also has some goodness that’s worth identifying and thinking about. This approach encourages the team to examine any idea for what might be useful and constructive. Doing so can help the team think more deeply about ideas as they emerge and to be open to alternate perspectives.

Identify Potential Solutions

As team members work together to deepen their understanding of a complex problem set, potential solutions and approaches to managing problems begin to emerge.

The activities involved in understanding complex problems and envisioning potential solutions are tightly intertwined and interactive. It is not unusual for a newly-imagined solution to reveal aspects of the problem that had gone unrecognized up to that point. The result is often additional effort spent to understand the problem more fully, along with shifts in the solution sets.

Here are some tips for envisioning potential solutions. They are based on research by the U.S. Army Research Institute with experienced Army leaders.

- Recognize that every problem set has unique aspects and requires a creative solution that is customized to the problem itself.

- Sketch it out. Drawing and other visual tools and techniques can help you think about potential solutions. Time spent drawing and thinking using non-digital tools can help you see the problem differently and think about it more deeply. Even simple visual tools can help the team anticipate “ripple effects,” future scenarios, or unintended consequences of taking a particular action.

- Use digital tools flexibly. Putting information directly into PowerPoint or other digital tools can constrain creative and innovative thinking about solutions.

- Leverage the pre-mortem technique and other red team strategies to vet the solutions or approaches you are considering. Doing so can help refine and improve the solution sets you are considering and often lead to new insights about the problem itself.

- Move your solution forward to detailed planning. Leverage resources, such as the Integrated Planning Handbook, to transition the work of understanding the problem and devising a solution to the work involved in creating detailed plans for execution.

- Ask yourself questions to evaluate the solution. Use reflective questioning to assess whether solutions are working as you intend, and how they might need to be refined. In some cases, you may find that your understanding of the problem needs to be re-framed. Example questions:

- What are the major changes in the environment since implementing our solution?

- How close are the changes to what we expected?

- What has taken us by surprise?

- What changes in the environment challenge our understanding?

- How should we update our assumptions based on the changes in the environment?

- How are we making sense of new information in our environment? (i.e., What are we learning?)

- What additional information do we need to reassess the environment?

- How do we reassess our course of action?

- If we change nothing, what do we expect?

Socialize ideas with stakeholders. Don’t wait until you have settled on a solution and finalized your products to share insights. Provide interim updates to key stakeholders as understanding and ideas evolve; share insights and interim work products.

Socializing ideas with stakeholders throughout the process provides an opportunity for you to expose stakeholders to your thinking, bring them along with you as understanding and insights evolve, and allows them to pose clarifying questions and weigh in on key decision points.

Socializing ideas can help you and your team refine your thinking. It also helps smooth the transfer of ideas and insights to those who will eventually need to act on them via detailed planning or execution.

Capture and Convey Insights

The work involved in making sense of complex problems and identifying possible solutions almost always takes place in the context of a larger organization, a higher mission, and at the request of one or more stakeholders.

Communicating your understanding, insights, and possible solutions to others is a key part of effectively managing complex problems. Conveying information in ways that are digestible, useful, and compelling is key.

Capturing and conveying insights to others can be challenging. Visualizing a complex problem in order to understand it is a distinctly different task from that of communicating your thoughts and insights. Moreover, the tools and products that may have been useful for discovery and developing understanding are not necessarily the best way to communicate your understanding to others.

Effective communication of your understanding means taking a fresh look at your insights and thinking about how to help people new to the problem set make sense of it.

Here are some tips for capturing and conveying insights. They are based on research by the U.S. Army Research Institute with experienced Army leaders.

Recognize the difference between interim and final products. The team’s interim analysis products and visual representations may make complete sense and be highly meaningful to the people who developed them. But internal work products that hold significant meaning for the team may not be useful or appropriate for communicating insights to stakeholders.

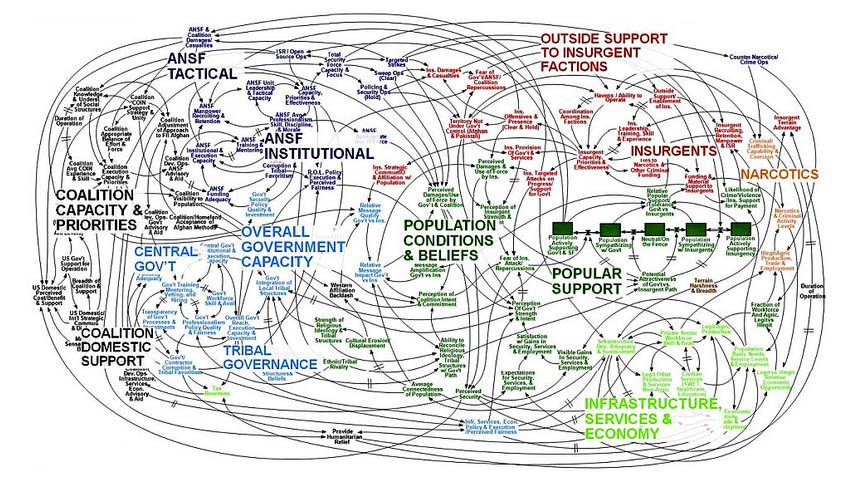

An example is a PowerPoint slide developed to depict the strategic challenges facing military forces in Afghanistan. It offered a lot of information, but little insight.

The U.S. military’s plan for Afghanistan stability and security – otherwise known as the “spaghetti slide” - published in the New York Times on April 27, 2010.

Interim work products are likely to need revision, additional explanation, or streamlining to boost the information they convey. Work products need to stand alone and make sense to key stakeholders, and they need to convey the meaning you intend.

Know your audience. Effectively conveying your understanding and recommendations requires that you know who the stakeholders are and their needs, styles, and preferences for consuming information. In the Army, the Commander is the primary stakeholder or end-user of your products. If you are the Commander, conveying your information preferences to your staff allows them to provide final products that are most useful to you.

If you are part of the Command staff, you may know your Commander’s preferences for consuming information, or be able to figure that out based on regular interactions with him/her. However, when there is a larger audience for your work, you may find it worthwhile to actively seek additional information by conducting a stakeholder analysis. To conduct a stakeholder analysis, consider the following questions:

- Who are the major stakeholders?

- What are their goals and needs?

- How will they use the products you are developing?

- What decisions will your team’s products inform?

- How might goals/needs of different stakeholders align or be in conflict with one another?

Use the answers to these questions to shape the information and products you provide for stakeholders. Doing so will allow you to convey your insights in ways that are most useful and effective.

Seek external feedback. Bring in someone from outside the team to review and provide a pair of “fresh eyes” on final products. One way of carrying out a sanity check is to ask your reviewer to explain back to the team the message he/she is taking away from the product. This technique allows you to assess whether work products communicate what you intend them to. It can help illuminate potential points of confusion or areas that need to be reconsidered or refined.

Consider alternative ways to package information. Although PowerPoint briefings are the standard approach for packaging and communicating information within the military, PowerPoint – and the associated briefing culture in the military – has important limitations (see “How PowerPoint stifles understanding, creativity, and innovation within your organization").

Other ways you might consider packaging information for stakeholders include:

- Infographics or other visual representations that depict ideas and recommendations using a combination of text and graphical media

- Single page stakeholder narratives that provide a non-bulleted, text-based description of insights and recommendations

- Conversation, using a quad chart or bulleted one-pager as an aid

- Storyboards

- Concept maps or mind maps

Decisions about how to package the information you want to convey should largely depend on stakeholders’ preferences for receiving information.

TOOLS AND GUIDES

A set of handbooks offer practical guidance related to managing complex problems. The information in the handbooks is based on interviews and observations, reviews, and feedback provided by 1) experienced Army personnel at a range of echelons, operational commands, and backgrounds, and 2) schoolhouse instructors and civilians (often retired Army) with deep knowledge about what it takes to manage complex problems in real world operational settings.

The tools and guidebooks contain a wealth of information on:

- The challenges that individuals and teams encounter working with complex problems

- Strategies and approaches that have proved useful for navigating those challenges

- Examples drawn from real-world experience

- Additional sources of information and guidance

Click on each of the icons below for more information.

You can also click here for a full list of reports, tools, and guides that informed this resource.

Expert Perspectives - Bios

LTG H. R. McMaster, Ph.D.

At time of recorded interview (January 2017), LTG H.R. McMaster served as the Director of the Army Capabilities Integration Center (ARCIC) and Deputy Commanding General, Futures of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command. He then went on to serve as the U.S. National Security advisor in March 2017. He has also previously served as Commanding General at the Maneuver Center of Excellence and Commander of the Combined Joint Inter¬Agency Task Force-Shafafiyat in Kabul, Afghanistan. He is known for playing significant roles in several overseas military operations, including the Gulf War, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom. LTG McMaster's military education and training includes the Airborne and Ranger Schools, Armor Officer Basic and Career Courses, the Cavalry Leaders Course, the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, and a U.S. Army War College fellowship at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. He holds a Ph.D. in American History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and is a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

At time of recorded interview (January 2017), LTG H.R. McMaster served as the Director of the Army Capabilities Integration Center (ARCIC) and Deputy Commanding General, Futures of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command. He then went on to serve as the U.S. National Security advisor in March 2017. He has also previously served as Commanding General at the Maneuver Center of Excellence and Commander of the Combined Joint Inter¬Agency Task Force-Shafafiyat in Kabul, Afghanistan. He is known for playing significant roles in several overseas military operations, including the Gulf War, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom. LTG McMaster's military education and training includes the Airborne and Ranger Schools, Armor Officer Basic and Career Courses, the Cavalry Leaders Course, the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, and a U.S. Army War College fellowship at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. He holds a Ph.D. in American History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and is a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Role at time of video recording: Director of Army Capabilities Integration Center

Date of recording: January 2017

Expert Perspectives - Bios

Colonel Paula Lodi

At time of recorded interview, COL Paula Lodi served as the Commander of the 44th Medical Brigade, Ft. Bragg, NC. She has 26 years of service in the U.S. Army, specializing in healthcare operations and multifunctional logistics. Her previous assignments include the Army staff at the Pentagon and Commander of the Special Troops Battalion, 15th Sustainment Brigade. She is a veteran of three tours in Iraq where she served as a Corps-level Operational Planner and as Executive Officer for a medical task force. Her service has also included humanitarian missions Operation Provide Comfort during the Gulf War and Hurricane Katrina relief. She holds Masters degrees in Military Operational Art and Science from the School of Advanced Military Studies, in National Security Policy Studies from the Naval War College, and in Public Administration from Troy University.

At time of recorded interview, COL Paula Lodi served as the Commander of the 44th Medical Brigade, Ft. Bragg, NC. She has 26 years of service in the U.S. Army, specializing in healthcare operations and multifunctional logistics. Her previous assignments include the Army staff at the Pentagon and Commander of the Special Troops Battalion, 15th Sustainment Brigade. She is a veteran of three tours in Iraq where she served as a Corps-level Operational Planner and as Executive Officer for a medical task force. Her service has also included humanitarian missions Operation Provide Comfort during the Gulf War and Hurricane Katrina relief. She holds Masters degrees in Military Operational Art and Science from the School of Advanced Military Studies, in National Security Policy Studies from the Naval War College, and in Public Administration from Troy University.

Role at time of video recording: Commander of the 44th Medical Brigade

Date of recording: February 2017

Expert Perspectives - Bios

Colonel (Ret.) Jim Greer, Ph.D.

Jim Greer is a Retired Army Colonel, serving 30 years in CONUS, Europe and the Middle East, including combat operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, Palestine, and the Balkans. COL Greer (Ret.) commanded an infantry-heavy battalion task force in Bosnia, led the Operation Iraqi Freedom Study Group in the invasion of Iraq, was Chief of Staff of MNSTC-I and commanded 1st Armor Training Brigade. He played a significant role in Army transformation for Force XXI digitization and the Objective Force, was the Army’s representative to DOD’s Revolution in Military Affairs and led the transformation of Initial Entry Training from a Cold War paradigm to one that prepared Soldiers for 21st Century combat. An educator and trainer, he taught tactics at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and was the Director of the School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS). COL (Ret.) Greer’s military and training education includes a B.S. from West Point, an M.S. in Educational Consulting at Long Island University, an M.S. in National Security from National War College, and a Ph.D. in Education from Walden University.

Jim Greer is a Retired Army Colonel, serving 30 years in CONUS, Europe and the Middle East, including combat operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, Palestine, and the Balkans. COL Greer (Ret.) commanded an infantry-heavy battalion task force in Bosnia, led the Operation Iraqi Freedom Study Group in the invasion of Iraq, was Chief of Staff of MNSTC-I and commanded 1st Armor Training Brigade. He played a significant role in Army transformation for Force XXI digitization and the Objective Force, was the Army’s representative to DOD’s Revolution in Military Affairs and led the transformation of Initial Entry Training from a Cold War paradigm to one that prepared Soldiers for 21st Century combat. An educator and trainer, he taught tactics at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and was the Director of the School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS). COL (Ret.) Greer’s military and training education includes a B.S. from West Point, an M.S. in Educational Consulting at Long Island University, an M.S. in National Security from National War College, and a Ph.D. in Education from Walden University.

Role at time of video recording: VP, Center for Senior Leadership & Design, Abrams Learning & Information Systems, Inc.

Date of recording: November 2016

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE: VIDEOS

Bios

Video Library

Filter on expert OR topic OR exercise

Expert:Topic:

Exercise: