X

Some example starter questions or phrases include the following:

Starter Phrases or Questions

Some example starter questions or phrases include the following:

- What do we know? What do we think we know? What do we need to know that we don’t know right now?

- What are we missing? What factors are we not accounting for?

- Let’s think about and discuss the strengths and limitations of this idea.

- What is the biggest question on your mind right now?

- Where does this idea fall short? Where is it most robust?

- Let’s think about how this assumption may (or may not be) valid; then let’s discuss.

- Help me understand your perspective better.

- What are the pros and cons for this idea/concept?

- Help me understand what I am missing. Where is my idea flawed?

- What are you puzzling most about right now?

- What connections or relationships are we missing?

- Everybody think of one drawback (or strength) of this idea/concept.

- How well does this model account for what we’re trying to understand? What is it missing?

- Where might we expand our research and learning?

- We’ve characterized this (phenomenon) as a problem about (X).

- Is this the right level?

- Should we be looking at a higher level? A lower level?

- You've observed this (phenomena). Why do you think it takes place?

- What are its possible causes?

- If the relationships are not cause/effect, are they still worth thinking about as probable associations?

- Should we be looking at a higher level? A lower level?

X

Role-clarification exercises allow team members to describe, discuss, and clarify what they bring to the team. The exercise provides an opportunity for members to think about and explicitly describe how they view their role(s) on the team, given what they understand about the team’s goal and their own skills, strengths, and experiences. It also provides an opportunity to highlight and deconflict areas in which the team leader or other team members may see an individual’s role differently, or see a connection between some aspect of their personal history and the team’s mission. Some example starter questions for role-clarification exercises might include:

Role Clarification Exercises

Role-clarification exercises allow team members to describe, discuss, and clarify what they bring to the team. The exercise provides an opportunity for members to think about and explicitly describe how they view their role(s) on the team, given what they understand about the team’s goal and their own skills, strengths, and experiences. It also provides an opportunity to highlight and deconflict areas in which the team leader or other team members may see an individual’s role differently, or see a connection between some aspect of their personal history and the team’s mission. Some example starter questions for role-clarification exercises might include:

- Given the team’s goals, how do you envision your role on this team?

- What do you bring to the team that is unique?

- “The way I envision your role on this team is…”

- “What I believe you bring to the team that is unique is…”

X

Campbell Leadership Descriptor $

Description: Self-assessment designed to help individuals identify characteristics for successful leadership, recognize their strengths, and identify areas for improvement.

Access: http://www.ccl.org/leadership/assessments/CLDOverview.aspx

MSAF360 – The Army’s Multi-Source Assessment and Feedback

Description: A 360° (i.e., multi-source) survey that provides individuals with feedback on their leadership strengths and areas for improvement. (CAC login required)

Access: http://msaf.army.mil/LeadOn.aspx

Multifactor Leadership Description Questionnaire (MLQ) $

Description: A questionnaire assessment that measures leadership types. Considered the benchmark measure of transformational leadership.

Access: http://www.mindgarden.com/products/mlqc.htm

Profiles of Organizational Influence Strategies (POIS) $

Description: An assessment tool that measures how people use influence within their organizations.

Access: http://www.mindgarden.com/products/pois.htm

SKILLSCOPE® Team Feedback Assessment $

Description: A 360° (multi-source) assessment checklist that provides individuals with feedback on job-related skills necessary for effectiveness in a leadership role.

Access: http://solutions.ccl.org/SKILLSCOPE

Leadership Assessment Tools

Campbell Leadership Descriptor $

Description: Self-assessment designed to help individuals identify characteristics for successful leadership, recognize their strengths, and identify areas for improvement.

Access: http://www.ccl.org/leadership/assessments/CLDOverview.aspx

MSAF360 – The Army’s Multi-Source Assessment and Feedback

Description: A 360° (i.e., multi-source) survey that provides individuals with feedback on their leadership strengths and areas for improvement. (CAC login required)

Access: http://msaf.army.mil/LeadOn.aspx

Multifactor Leadership Description Questionnaire (MLQ) $

Description: A questionnaire assessment that measures leadership types. Considered the benchmark measure of transformational leadership.

Access: http://www.mindgarden.com/products/mlqc.htm

Profiles of Organizational Influence Strategies (POIS) $

Description: An assessment tool that measures how people use influence within their organizations.

Access: http://www.mindgarden.com/products/pois.htm

SKILLSCOPE® Team Feedback Assessment $

Description: A 360° (multi-source) assessment checklist that provides individuals with feedback on job-related skills necessary for effectiveness in a leadership role.

Access: http://solutions.ccl.org/SKILLSCOPE

CORE ACTIVITIES

Recognize Complexity

How can I tell if problems are complex? Why does it matter?

It is not always clear that you are dealing with a complex problem. Many complex problems may seem fairly simple on the surface, or when you first encounter them. People also have a tendency to underestimate complexity.Problems that are not complex are well-defined and have clear boundaries. Solving them might require significant time and effort, but there is a clear path to a solution.

With complex problems, that isn’t the case. When dealing with complex problems, the very nature of the problems are typically unclear and ill-defined.

Misjudging complexity and developing solutions for a simplified version can actually cause problems to worsen. A solution that is appropriate for a simple version of a problem set is unlikely to address all of the factors that must be considered in order to address it effectively.

“The inability to identify complex problems and understand why they are complex significantly hampers effective visualization of such problems.”

-Experienced Army Planner

Individuals, leaders, and organizations often do not realize they are facing complex problems until they begin trying to address them. They find that solutions that seemed well-crafted do not have the intended effects. There may be surprising outcomes or unintended consequences. These are indicators that the problems are more complex than originally thought.

Individuals, leaders, and organizations often do not realize they are facing complex problems until they begin trying to address them. They find that solutions that seemed well-crafted do not have the intended effects. There may be surprising outcomes or unintended consequences. These are indicators that the problems are more complex than originally thought.

Recognizing early on that a problem set is complex allows you to allocate resources in order to understand it and approach it more fully. To recognize complex problems, consider these questions:

- Are multiple players involved?

- Is there a time dimension that is critical?

- Are the problems fluid, so that aspects of the problems are changing rapidly?

- Are there a variety of factors at play – e.g., cultural, social, political, economic aspects?

- Are multiple – potentially competing – goals in the mix?

- Is it possible that the problems are a symptom of another, even larger problem set?

- Are there second-and third-order effects (ripple effects) that need to be considered?

- Are the problems nested, or intertwined, with another problem or set of problems?

- Do experts disagree about the nature of the problems and the solution?

“…Everybody wants to simplify everything these days …Can you give that to me in one page? …in one bullet?"

Some of the PowerPoint charts in Iraq would say [things like] "Sectarianism -- a continuing problem. Iraqi security forces need a way ahead." What is that? We oversimplify things and as a result, we really don't understand how what we're doing is relating to progress or lack of progress in the overall effort. I think that we all need to think more deeply about problems and resist the tendency to oversimplify these very complex problems.”

- LTG H.R. McMaster

Understand Complex Problems

What can help me understand and visualize complex problems?

One of the most important activities to help you make sense of a complex problem is to think holistically about the problem.Take a step back. “Zoom out.” Consider the larger context in which the problem is embedded, the environmental framework that surrounds it. Consider what else the problem is connected to and how.

Experienced commanders, planners, and strategic thinkers offer a number of recommendations for how to begin deepening your understanding of a complex problem. Here is a set of suggestions to consider:

Use an approach, such as Army Design Methodology (ADM), to define the problem and the desired goals or outcomes before moving into problem solving and detailed planning. ADM is part of Army doctrine. To understand how to bring ADM and more detailed planning together, see the Integrated Planning Handbook.

Prepare your mental and physical workspace: When making sense of complex problems, it is important to get yourself ready to think holistically, critically, and creatively. It is also important to arrange for a physical workspace and materials to work with that are conducive to collaboration, discourse, and co-creation of meaning. A few suggestions include:

- Think about thinking. Reflect on the perspectives, worldviews, and biases you bring to the team. To help you do this, consider using some of the tools and inventories that assess aspects of cognitive style, preferences for learning and information processing, personality type, and interaction styles. These tools can help increase your self-awareness about the way you typically think and approach problems.

- Prepare for ambiguity. Complex problems are full of ambiguity and making sense of them can be confusing work. Teams manage that confusion and ambiguity better when they know to expect it and understand that it is normal. Rather than seeing moments of confusion and uncertainty as signs of trouble or failure, they can be the impetus for significant learning and novel insights.

Find or create a physical space that allows for:

- Independent work such as research and quiet reflection

- Group work such as discourse, discussion, and sharing ideas

- Individual and group visualization activities and access to shared content (e.g., whiteboards, wall space)

- Making a mess, using materials such as post-its, images, collages, and sketchpads

- Reconfigurable space that supports different work modes and team activities

- Face-to-face interaction during discussion, such as seating in a horseshoe or circular configuration

Gather materials and tools the team can use to visualize and determine approaches for solving complex problems. These might include:

- Whiteboards (multiple boards, if possible)

- Wall space where materials can be posted

- Pens, pencils, and dry-erase markers of multiple colors

- Tangible working materials – such as a set of images, shapes, connectors, words, arrows (Example toolkit)

- Flipcharts, Sticky tack or tape

- Post-its, sketchpads, notebooks

- Camera(s), laptop(s), projector(s)

- Modular furniture, comfortable chairs

Once your workspace is prepared, the real work of making sense of a complex problem begins. Asking questions, gathering information, engaging in discourse, and creating visual representations of problems are all powerful ways to understand a complex problem more fully. Suggestions include:

Once your workspace is prepared, the real work of making sense of a complex problem begins. Asking questions, gathering information, engaging in discourse, and creating visual representations of problems are all powerful ways to understand a complex problem more fully. Suggestions include:

- Pose starter questions: A way to get started is for team members to generate all the questions they can think of regarding the current situation. Use those questions as a basis for reflection, team discussion, and information-gathering. Another strategy is to use a set of starter phrases or questions to seed the team’s initial discussions.

- Seek a variety of sources: Gather information widely—from books, periodicals, news outlets, social media, and subject matter experts (SMEs) with knowledge about the problem you are trying to understand. What’s important is to intentionally seek information from a variety of sources that reflect different points of view.

Create a positive climate for discourse and lively debate. Energetic exchange of ideas can help a team expand its learning and achieve deeper understanding of a complex problem. Commanders and other leaders have a critical role in creating a climate in which it is accepted and expected that individuals share and critique ideas freely. For more on the role of discourse, see The Power of Discourse.

Consider the following questions as you reflect on whether you’re contributing to a climate of respectful discourse:

- Are you encouraging participation of all ranks and downplaying the importance of hierarchy?

- Are you inviting others to disagree with your ideas and question your assumptions? (e.g., “Someone challenge me on my assertion. What am I missing?”)

- Are you actively seeking different perspectives?

- Are you using a respectful tone and language in your critiques and disagreements?

- Are you listening actively when others are talking and seeking clarification when needed?

“We can always be learning. There are always things we didn't consider and things that will connect in ways that we hadn't envisioned.”

-COL Paula Lodi

Need help building your skills in holistic/systems thinking? See Telling a Story: An Exercise in Connecting the Dots

Use visual tools (e.g., whiteboards, markers, graphics, images, shapes, post-it notes, connectors) to explore the problem and help your team think more deeply about it. Consider using techniques such as mindmaps, fishbone diagrams, or concept maps. Click here for some examples. Many people think differently and have different kinds of insights when they work with visual representations. Visual tools will help you think more holistically, consider relationships among elements of the problem, and communicate your evolving understanding to other team members. Some suggestions:

- Recognize the limitations of certain tools. PowerPoint and other software have important uses, but they can stifle critical thinking and creativity, and impede understanding of complex problems.

- Remind yourself and others that artistic talent is not a requirement. People sometimes feel intimidated about going to the whiteboard and drawing their ideas. Remind team members that visualization can be rough and sketchy and still communicate important ideas. It’s not about creating good art, but about using a visual language to achieve new insights on the problem.

“Being able to think about complex systems in a holistic way and to be able to think about how those factors interact and how they interact with you and your efforts is critically important.”

-LTG H.R. McMaster

Collaborate With Others

How do I lead or work with a team to manage complex problems?

The work of understanding and solving complex problems is rarely - if ever - done by a single individual. Complex problems by their very nature require teams - and often teams of teams - to develop a deep and comprehensive understanding of a problem and how to address it.Recommendations for working in teams to understand and manage complex problems include:

Assemble a team with diverse perspectives. Teams with limited diversity - where everyone on the team tends to think the same way - have a much harder time understanding complex problems or developing innovative solutions. Bringing together individuals with different perspectives, backgrounds, knowledge, diverse thinking styles, and personality characteristics will increase the likelihood that new connections and insights will occur.

In assembling a team to work on a complex problem, look for people who have these skills and attributes:

- An open mind and room for new ideas

- An inquisitive mindset; who are curious and eager for knowledge

- Avid readers with an ability to digest and synthesize large amount of information

- Comfortable with ambiguity

- Creative-and innovative-thinking skills

- A willingness to listen to others

- Respect for differing points of view

- Ability to look at the problem from different perspectives

- Research/investigative skills

- Willingness to speak up and share their point of view

- Ability to think and communicate ideas both verbally and visually

- Comfortable with and eager to have their ideas critiqued

Make roles explicit. Army leaders with experience managing complex problems have found that teams work more effectively when specific team members are designated to take on the following roles:

- Capture the discussion in text notes

- Capture ideas in visual form— i.e., graphics

- Think about and develop metrics— i.e., how you might test the insights you develop

- Lead and monitor the team process

- Play devil’s advocate, with the specific task of questioning the team’s assumptions

- Manage information on current operational constraints and evaluate the feasibility of proposed approaches or solutions

Consider the role of the Commander. In complex problem-framing and -solving activities, the Commander has a critical role in providing guidance and setting constraints for his/her staff. Commanders have multiple, competing demands for their time and attention, and often cannot participate in day-to-day work of the team. Given this reality, experienced Commanders have suggested reflecting on the following questions in order to provide guidance:

- What will the level and nature of my involvement be in the activity?

- If I cannot be involved in all aspects, what are the critical parts to be involved in? Where can I have the greatest impact?

- If I cannot be involved in all aspects, how do I want the team to communicate their logic and insights to me? How frequently? And in what format? (Do I want a set of PowerPoint slides? A narrative description? A graphic? An email with bullet points? A combination of these formats?)

In parallel, the staff has an important role in determining when it’s critical to bring the Commander into the discussion.

Facilitate relationship-building. Provide opportunities for team members to interact socially and to build trust. One possibility is to build the team through personal-story-telling and role-clarification exercises. One way to do that is to invite each team member to describe his/her background and experiences, and the strengths and skills they bring to the team.

Agree upon and monitor the team dynamic. An important part of creating an effective team is guiding the team to self-manage. That might include occasional reflection and discussion about how the team wants to operate, and how things are going. For example, are there particular work processes and ways of working together that the team sees as most productive? Certain kinds of interaction among team members that the team thinks are beneficial (or not helpful)? Are there aspects of how team members interact that are getting in the way of its effectiveness, or that are particularly helpful? Engaging team members as active participants in monitoring and adjusting how the team functions has ongoing benefits for how the team operates, and the quality of its work.

“No matter what you prepare for, the Army will always give you a problem that you had never considered previously. Constantly engaging multiple sources of information gives you a much better foundation from which to react when confronted with a problem that you had never previously considered.”

-COL Paula Lodi

- “The point I made doesn’t seem to be resonating with you. Help us understand what you’re thinking.”

- “You seem to be disagreeing with that concept. Help us understand where our ideas aren’t aligning.”

- “Tell us why that idea doesn’t make sense from your perspective.”

Use a “spectrum policy” approach to vetting ideas. The spectrum policy acknowledges that all ideas or viewpoints have both good (useful) and bad (not useful) aspects. Whatever the degree of “badness” there might be, any idea also has some goodness that’s worth thinking about. Instead of responding with “that won’t work because…” or “that doesn’t make sense because…” encourage the team to look at the idea as a spectrum, and pick out a good part of it to build upon constructively. This can help the team think more deeply about ideas as they emerge. It also keeps the owner of the idea engaged, and preserves team momentum.

Identify Potential Solutions

How do I develop solutions to complex problems?

Einstein said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.” As the team invests effort into understanding a complex problem deeply and holistically, potential solutions and approaches to managing the problem begin to emerge. In fact, the activities of understanding the problem and envisioning potential solutions are tightly intertwined and interactive.A newly imagined solution may reveal aspects of the problem that had gone unrecognized and result in additional effort spent on understanding the problem.

As you work with your staff to understand complex problems and envision potential solutions, it can be helpful to:

- Remember that every problem has unique aspects, and requires a creative solution that is customized to the problem itself.

- Sketch it out. Similar to using visual tools to understand the nature of the problem, use drawing and other visual tools and techniques to envision potential solutions to the problem. Given the strong connection between hand and brain, put most of your time and effort into drawing and thinking using non-digital tools. Using even basic visual tools to envision solutions can help the team anticipate “ripple effects,” future scenarios, or unintended consequences of taking a particular action to address the challenge.

- Use digital tools sparingly. Recognize that putting information directly into PowerPoint or other digital tools can constrain creative and innovative thinking about solutions.

- Leverage the pre-mortem technique and other red team strategies to vet the solutions or approaches you are considering. Use the insights gained from these approaches to iterate upon and refine your approach for addressing the problem. These review and refinement strategies can lead to new insights about the problem itself. Teams sometimes discover layers to the problem that they hadn’t seen before.

- Move your solution forward to detailed planning. Leverage resources, such as the Integrated Planning Handbook, to transition the work conducted for understanding the problem and devising a solution, to the work of creating detailed plans for execution.

- Ask yourself questions to evaluate the solution. As you begin implementing your solution, use reflective questioning to test how it is working. Questions such as those provided here can help you assess whether your solutions are working, and how they might need to be refined. In some cases, you may find that your understanding of the problem needs to be re-framed.

“You have to be able to envision the application of resources and efforts over time, and to envision how your efforts are going to interact with this very complex environment, not only determined enemies but other complex factors: political, social, cultural, historical dynamics, economic factors that affect the situation overall.”

-LTG McMaster

Capture and Convey Insights

How do I share my understanding of a problem with others?

Making sense of complex problems and envisioning solutions to them never happens in isolation. It always takes place in the context of a larger organization, a higher mission, and at the request of one or many stakeholders.Communicating your understanding, insights, and possible solutions to others is a key part of managing complex problems. Conveying information in ways that are digestible, useful, and compelling is key.

Capturing and conveying insights to others can be challenging. The processes involved in visualizing a complex problem in order to understand it and sharing that understanding with others are distinctly different (though clearly related) tasks.

The tools and products that you find useful for discovery and developing understanding are not necessarily so useful for communicating that understanding to others.

In addition, tools that are relied upon heavily in the Army, such as PowerPoint, may actually constrain your ability to share insights, visualizations, and ideas related to complex problems.

The following practical guidance - derived from experienced Commanders, planners, and design thinkers - can help you to be successful in capturing and conveying insights to stakeholders:

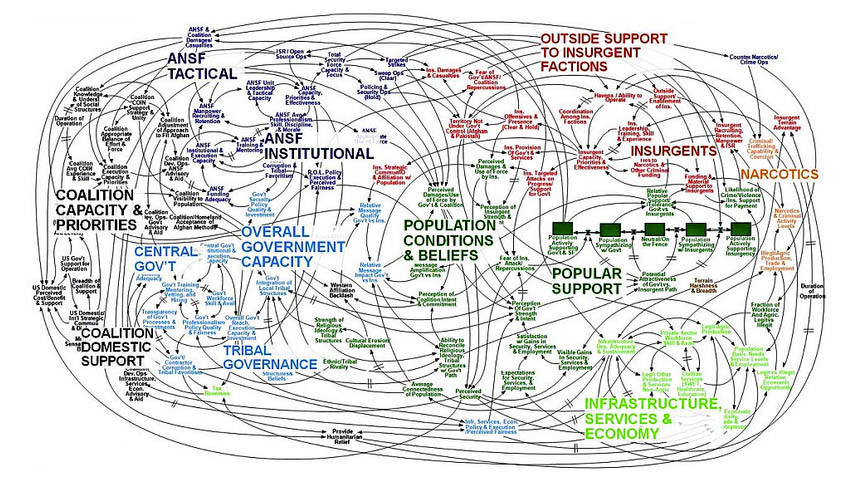

The U.S. military’s plan for Afghanistan stability and security – otherwise known as the “spaghetti slide” - published in the New York Times on April 27, 2010.

Recognize the difference between interim and final products. The graphic you and your team created to help you think about the problem will not necessarily make sense or be useful to people outside your team. At the very least, those products are likely to need revision or additional explanation. This point is exemplified by the now-familiar spaghetti diagram developed to depict the strategic challenges facing military forces in Afghanistan.

Know your audience. Effectively conveying the understanding and recommendations your team has developed requires that you understand your stakeholders’ needs, styles, and preferences for consuming information. In the Army, the Commander is the primary stakeholder or end-user of your products. If you are the Commander, convey your preference for consuming information so that your staff has a target for their final products.

If you are part of the Commander’s staff, you may know your Commander’s preferences for consuming information, or be able to figure that out based on regular interactions with him/her. However, you may find it worthwhile to actively seek additional information about your audience through a stakeholder analysis.

Conduct a stakeholder analysis by considering:

- Who are your stakeholders?

- What are their goals and needs?

- How will the stakeholders use the products you’re developing?

- What decisions will your team’s products be informing?

- How might needs of diverse stakeholders align or be in conflict with one another?

- What does that mean for the product(s) the team ultimately provides for stakeholders?

Seek external feedback. Consider bringing in someone from outside the team to provide a “sanity check” on final products. This person might be resident within the organization, or someone the members trust from outside the immediate organization. One way to check on how well products communicate what the team intends them to is to ask your reviewer to explain back to the team the message he/she is taking away from the product. This technique can help illuminate potential points of confusion or areas that need to be reconsidered or refined.

Consider alternative ways to packaging information. Although PowerPoint briefings are the standard approach for packaging and communicating information within the military, PowerPoint – and the associated briefing culture in the military – has important limitations (see “How PowerPoint stifles understanding, creativity, and innovation within your organization").

Other ways you might consider packaging information for stakeholders include:

- Infographics or other visual representations that depict ideas and recommendations using a combination of text and graphical media

- Single page stakeholder narratives that provide a non-bulleted, text-based description of insights and recommendations

- Conversation, using a quad chart or bulleted one-pager as an aid

- Storyboards

- Concept maps or mind maps

See the "Knowledge Management" section of the Design Metrics Handbook or Making Sense of Complex Problems: A Resource for Teams for additional tips and details about capturing and conveying insights to stakeholders.

Socialize ideas with stakeholders. Don’t wait until you have completed your products to share insights. Provide interim updates to key stakeholders as understanding and ideas evolve.

Socialize ideas with stakeholders. Don’t wait until you have completed your products to share insights. Provide interim updates to key stakeholders as understanding and ideas evolve.

Socializing ideas with stakeholders throughout the process provides an opportunity for you to expose stakeholders to your thinking, bring them along with you as understanding and insights evolve, and allows them to pose clarifying questions and weigh in on key decision points.

Socializing ideas can help you and your team refine your thinking. It also helps smooth the transfer of ideas and insights to those who will eventually need to act on them via detailed planning or execution.