Exploring and Learning as a Team

At the beginning of a conceptual planning effort, teams face the challenge of beginning to understand the problem set, while also acknowledging that “they don’t know what they don’t know.” The team may be starting with a conceptualization of the problem set that is overly simplistic and possibly off-base. Preliminary discussions among team members at this stage allow members to share current thinking and assumptions about the problems, and to begin the process of intensive information gathering, reading, and reflection.

“During the first step of any problem solving effort, you’ve got to read more than you talk... You must study your head off initially to grasp the essence of the problem.”

(USMC LtCol)

Virtually all of the team leaders and team members we interviewed described engaging in an iterative and flexibly-organized set of activities for exploring and learning as a team that continued across the span of the effort. Learning as a team involves a mix of individual study and reflection interspersed with collaborative dialogue including knowledge sharing, capturing insights, critiquing concepts, and creating knowledge products and representations of the problem set’s complexities.

Key Issues and Challenges

The primary forum for the group’s discussion, critique, and exchange of ideas is the team’s discourse. Productive discourse is the catalyst that drives high functioning teams to generate new ways of thinking about the problem set, and to identify innovative solutions. Discourse is typically described as a way for team members to question one another’s ideas, and to refine the team’s thinking. And while discourse does have those impacts when it is done well, it has a number of additional benefits. For example, effective discourse:

- Reveals the assumptions that underlie an argument or concept and reveals where team members may be biased in their current thinking. Also reveals what members might not be thinking about in regards to the problem set.

- Displays the diversity that exists in the team and gives exposure to a range of viewpoints; it offers team members the opportunity to explore a concept from differing perspectives.

- Reveals areas where the team may lack diversity or sufficient experience, and where external SMEs could be valuable.

- Is a basis for developing shared mental models (Note) across the team that support the deep understanding of a problem space that teams are working toward.

- Allows the team to identify boundaries and intersections between different areas of knowledge and cultural understanding. Finding creative solutions to complex problems often occurs at the boundaries between disparate areas.

- Is an important basis for building trust in the team and the team’s processes.

As central as discourse is to the team’s learning efforts, conducting effective discourse within the team is not without its challenges. Planning teams face a variety of obstacles to effective discourse (see Leading the Team), and Commanders and team leaders play a central role in breaking down those barriers and creating an environment within the team that enables frank discourse to take place.

In addition to discourse, experienced team leaders and members identified cognitive flexibility as a critical facet in developing a shared understanding of complex problems. Cognitive flexibility is the ability to adjust how the team is thinking about the problem space in response to new information or shifting goals. Cognitive flexibility reflects an adaptive style of thinking that allows teams to engage in different modes of thinking, and to incorporate diverse and sometimes opposing points of view into their understanding of a problem space. A deeper understanding of the problem becomes possible when and if the team is able to step away from its current perspective, re-examine the team’s assumptions and mental models, and shift to a different framework for understanding the problem set.

In exploring problems as a team, it is important to be purposeful about engaging in different modes of thinking. Some examples of different ways of thinking described by experienced team leaders and members are:

“As we begin to learn more about our subject, we begin to conclude our problem is different than what we’re trying to solve, that the problem needs to be reframed. That leads to the first moment of challenge. Everyone has met and agreed that we’re going to address problem x, but the real problem is different or much more complex.”

(Civilian Designer)

- Thinking about Thinking

This Is also known as metacognitive thinking and reflects a person’s awareness of his or her thinking style, usual paradigms or frames of reference, and associated biases. Thinking about how one thinks encourages individuals (and the team as a whole) to be explicit about the “frame(s)” they are using to understand a problem set. When teams are able to reflect upon and be explicit about how they are thinking about the problem, it allows them to also understand what they might not be thinking about — and to consider alternative points of view that might be important for appreciating the complexity of the problem set. - Thinking Holistically

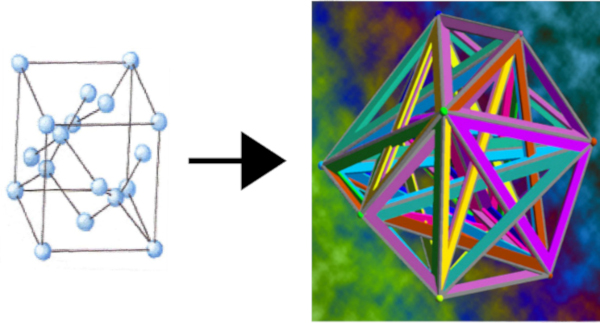

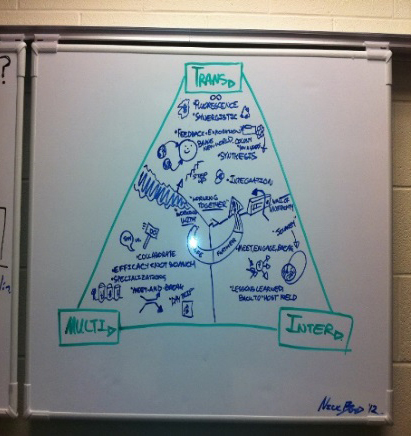

In holistic or systems thinking, the team reflects on how components of a problem set relate to and influence each other, and how the components connect to the larger context (or system) of which they are a part. Holistic thinking is inherently integrative, and is important for helping teams break away from linear cause-effect and compartmentalized ways of addressing the problem (i.e., considering components of the problem set in isolation). When teams are able to adopt a systems-level view, members are able to see subtleties, indirect influences, and interactive effects that may be critically important for appreciating the problem’s complexity and anticipating 2nd or 3rd order effects of possible actions. - Thinking Expansively to Resolve Differences

Another approach reflects the way the team and its leader manage differences of opinion across the team. One team leader described her refusal to accept either compromise among the team, or voting for the best idea. Instead, she insisted that the team continue working away at the problem and the potential solutions until the team had identified concepts with which all team members could agree. The team expanded their thinking until it was able to encompass divergent points of view.

“I refused to allow it to become a voting situation, which is what the other guys wanted. [Voting] is an American cultural thing, where the best guy wins. [In this case] robust ideas are put forth and advocated for, and the best idea wins. I refused to ok [a process of] ideas winning, [or] a compromise where you water down an idea, or one idea won or lost. It had to be a 3rd way that everyone could agree to. That was the most frustrating thing to other guys on the team. Win or lose they wanted a decision. But I think we came out with a much better product because of that.”

(U.S. Army COL)- Perspective Taking

Perspective taking requires understanding the thoughts, feelings, and motivations of others and examining the problem space from another’s point of view. This can be particularly important in operational contexts where the culture is considerably different from the team’s cultural composition. Team members may have the tendency to think about the problem space from a U.S. Western point of view, rather than from the point of view of individuals and groups operating from a different cultural perspective. Taking the perspective of others can help to understand important connections and rationale that may be otherwise missed.

- Thinking Visually

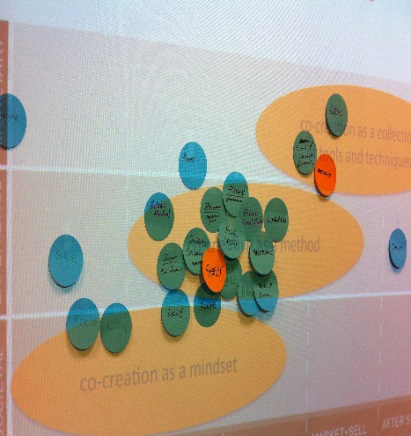

Visual thinking involves thinking and communicating using images and pictures, as opposed to thinking and communicating using language and text alone. Individuals and teams who engage in visual thinking use graphics and imagery to represent ideas and to explore the problem space. Thinking visually can yield rich and varied insights into complex and unfamiliar problems; teams are often surprised at how powerful visual thinking can be and how differently members can understand problems when they use a visual language to explore a problem set.

- Interestingly, many of the team members we interviewed described the importance of having access to whiteboards and markers for working through problems and as a collaborative workspace for representing situations, concepts and problems graphically. Some team members also described the value of having people on the team who can think visually. However, our discussions rarely went much beyond those two aspects of visual thinking. In addition, when visual tools were used, they tended to be used for creating and representing the teams’ understanding at the end of the conceptual planning activity, rather than as a tool to help the team explore concepts and achieve fresh insights.

Each of the aforementioned modes of thinking can be incorporated into discourse sessions and independent reflection to encourage cognitive flexibility, enhance understanding, and help the team achieve innovative solutions. All of these modes of thinking require practice and support. Some of the strategies for helping team members to become more mentally agile are discussed in the Tips and Things to Consider section.

Tips and Things to Consider

There are several strategies, tools and techniques for helping a team make sense of an unfamiliar problem set and explore its complexities. We note a number of them next, organized into two topic areas: Engaging the team in productive discourse and fostering mental flexibility.

(Expand All)

Engaging the Team in Productive Discourse:

- Use starter questions

- Identify a set of topics to explore

- Model the discourse process

- Consider appointing a devil’s advocate or red team representative

- Encourage the team to view moments of confusion as informative

- Guide discourse towards discussions that expand the team’s understanding

- Recognize when the team needs a break

- Vary the setting

- Set norms for the discourse interaction

- Respect silence

- Encourage team members to use notecards or notebooks

- Elicit chains of reasoning

- Identify key issues, learning, insights, and questions

Fostering Mental Flexibility:

- Think about thinking

- Provide a variety of tangible work materials

- Actively consider and discuss alternative points of view

- Resist voting on the “best” idea

- Use visual tools and techniques to explore the problem space, not just for depicting insights

- Consider using customized toolkits

- Combine and layer visual tools

- Remind the team that artistic talent is NOT needed

Tools and Resources

This section includes a set of tools and resources to supplement the topics covered in the “Engaging the problem as a team” module of this resource. This is not intended to be a comprehensive list of resources; but it provides a starting point for helping planning teams explore the problem space as a team and capture the team’s evolving understanding. The resources are organized according to the following topics: 1) visual thinking resources, 2) videos, 3) exercises, and 4) suggested reading.

Visual Thinking Resources

Periodic Table of Visualization Methods

Description: Examples of a variety of visualization methods organized like the Periodic Table of the Elements. Example visualizations can be accessed by clicking on each element.

Visual Complexity.com

Description: A resource for those interested in visualization of complex networks and visualization methods. Provides a series of examples of how others have visualized their findings and insights.

idiagram – The Art of Complex Problem Solving

Description: Visual approaches to help people think holistically about complex problems and communicate to those who must act on the problems. Examples of how others have represented complex problems can be accessed by clicking on links on left side of screen.

Maketools.com and Example toolkits [PDF]

Description: Source for ideas and visual toolkits for fostering collective creativity. See “Managing Complexity Collaboratively” to view visual toolkits in use.

Neuland.com

Description: Source for purchasing visual thinking and communication tools.

Visual Explorer Images [Product Listing]

Description: A set of images available for purchase to support teams in engaging in creative conversations and achieving new insights. See “Visual Explorer with David Horth” for more on Visual Explorer.

Videos

The Art of Data Visualization

Description: PBSoftBook digital series video that discusses the role of visual strategies to communicate information.

Exercises

Everyday Creativity Exercise [PDF]

Description: Helps team members recognize where and how their creativity is being expressed in everyday life, so they can then apply that way of thinking and being to their work.

Six Thinking Hats

Description: Exercise to encourage team members to look at a problem from different perspectives.

Art of Design, Student Text version 2.0 [PDF]

Description: School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS) text on design that provides multiple practical exercises and tools in Appendix B – e.g., Six Thinking Hats, Challenging Assumptions, Mind Mapping, Challenging Boundaries. See pp. 286-319.

Suggested Readings

The practice of creativity : A manual for dynamic group problem solving

Author: G. Prince

Asking the right questions. A guide to critical thinking

Author: M. Browne and S. Keeley

ISBN-10: 0205111165; ISBN-13: 978-0205111169

The ten faces of innovation: IDEO’s strategies for defeating the devil’s advocate and driving creativity throughout your organization

Author: T. Kelley and J. Littman

ISBN-10: 0385512074; ISBN-13: 978-0385512077

Six thinking hats

Author: E. de Bono

ISBN-10: 9780316178310; ISBN-13: 978-0316178310

Visual language: Global communication for the 21st century

Author: R. Horn

ISBN-10: 189263709X; ISBN-13: 978-1892637093

Convivial toolbox: Generative research for the front end of design

Author: E. Sanders & P. Stappers

ISBN-10: 9063692846; ISBN-13: 978-9063692841

Visual leaders: New tools for visioning, management, and organization change

Author: D. Sibbet

ISBN-13: 978-1118471654

Teams: Graphic tools for commitment, innovation, and high performance

Author: D. Sibbet

ISBN-10: 1118077431; ISBN-13: 978-1118077436

Dialogue mapping: Building shared understanding of wicked problems

Author: J. Conklin

ISBN-10: 0470017686; ISBN-13: 978-0470017685

The back of the napkin (Expanded Edition): Solving problems and selling ideas with pictures

Author: D. Roam

ISBN-10: 1591842697; ISBN-13: 978-1591842699

Blah, blah, blah: What to do when words don’t work

Author: D. Roam

ISBN-10: 1591844592; ISBN-13: 978-1591844594

Stir symposium

Author: Stir Symposium

ISBN-13: 9780615583488

Does design help or hurt military planning: How NTM-A designed a plausible Afghan security force in an uncertain future, Part I [PDF]

Author: B. Zweibelson